POST 244 --- BLACK ORCHID

- Scott Cresswell

- Nov 5, 2023

- 10 min read

The 1980s is commonly remembered as a decade of new concepts and seismic creative sparks which shook the comic book medium to its core. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s Watchmen come to mind, but looking back, it’s stunning to witness how such a large number of these era-defining stories feature or focus on characters who had been created in previous decades by run-of-the-mill writers and artists. While Alan Moore created a flawless earthquake in his Swamp Thing run during the eighties, the star character had existed for a decade. Later, Grant Morrison would arrive and make the headlines with Animal Man and Doom Patrol, two concepts from the 1960s. Even Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns – now considered, alongside Watchmen, to be the ‘graphic novel’ which launched comics into adulthood – was a success due to its primary protagonist, a character created in 1939. The 1980s was a period of success not sorely because new characters were created, but also because existing ones were updated, revamped, and relaunched with new twists. Many of the relaunched characters enjoyed little time in the spotlight, let alone any popularity in their day. One of those was Black Orchid…

Black Orchid was a three-issue miniseries published from December 1988 to February 1989. Written by Neil Gaiman, it was painted by Dave McKean. Although originally released as a DC Comic, it has subsequently been reprinted under their Vertigo imprint.

Today, Neil Gaiman is remembered at DC Comics most commonly for The Sandman, a title from 1989 to 1996 which lasted for 75 issues. But before he found this fame, he had been a writer and journalist on friendly terms with Alan Moore, just as he was making waves in the United States. In 1987, Gaiman met Karen Berger, an editor at DC who later enjoyed a pivotal role in the creation of Vertigo Comics. Brimming with ideas and concepts, Neil Gaiman was given a miniseries and with it he created a revamped and new version of Black Orchid. Unlike Swamp Thing, the Sandman, Animal Man, Doom Patrol, or pretty much any other title or character published by DC, Black Orchid was totally forgotten. Appearing in three issues of Adventure Comics during 1973, she was a master of disguise with a love of nature and plants. And that’s really about it. It certainly wasn’t a unique concept, and little of substance was ever written for the character. But perhaps, despite all of that, it was ideal for Gaiman. Moore had turned a failing plant creature into a success, and Morrison was doing the same with a man who could copy the powers of any animal. Could Gaiman succeed with a plant lady?

It perhaps goes without saying that you do not need to have read any previous Black Orchid stories from Adventure Comics. If you’re part of that very small minority, then I suppose more power to you! Throughout, Gaiman introduces us to the premise of Black Orchid’s original tales, but his three-issue miniseries is certainly a distant land away from the days of Adventure Comics.

Part of Black Orchid’s character was her love of costumes and disguise. With issue one, Gaiman plays with that immediately. Going undercover in an organised crime syndicate, Black Orchid is face-to-face with the crime boss of the city. She is revealed in a board meeting and instead of torturing her or threatening her with violence like in the James Bond movies, this crime boss simply fires a bullet into her. For extra measure, he douses her in gasoline and sets the whole building alight. In effect, the story starts with Black Orchid’s death. This is no Grant Morrison ploy, whereby we’re treated to an event later in the story and then the following pages are spent displaying the build-up to such a cataclysmic event. In this case, Black Orchid is killed. It’s an undeniably powerful beginning that leaves a mark.

Doctor Philip Sylvian is, in some respects, the Ben Kenobi of this tale. After Black Orchid’s death, another violet woman emerges from a greenhouse awake for the first time. Clones and their creation have become something of a dreary and overdone concept in comic books, but an interesting point of focus for this clone is her amnesia. Without any knowledge of Black Orchid, who she is, and what her story is, Gaiman spends much of the miniseries exploring an origin story that the original creators never told. Susan Linden, once the wife of Philip, was the original Black Orchid from the Adventure Comics issues. A superhero who fought crime, she was killed and subsequently, Philip experimented with her DNA and created augmented clones of her, keeping them in a nearby greenhouse. It’s amazing how Gaiman can write such a concept of sheer silliness yet deliver it in a veil of seriousness. It may be down to the gritty artwork, or perhaps the layer of emotion that Gaiman adds with Philip, or even the convincing amnesia that is placed within Black Orchid’s clone. Whatever the case, Gaiman ties this in beautifully to the expansive DC Universe. Philip and Susan were – at university – friends with up-and-coming scientists, such as Jason Woodrue, Pamela Isley, Alec Holland, and his wife Linda. Fans of titles like Swamp Thing and Batman will recognise these names, and it’s through this group that the new Black Orchid goes on her quest to discover who she really is. It’s a good premise for character development, but it’s slightly odd, especially since Philip told her everything, she really needs to know about herself. After issue one, little else of value is conveyed about Black Orchid.

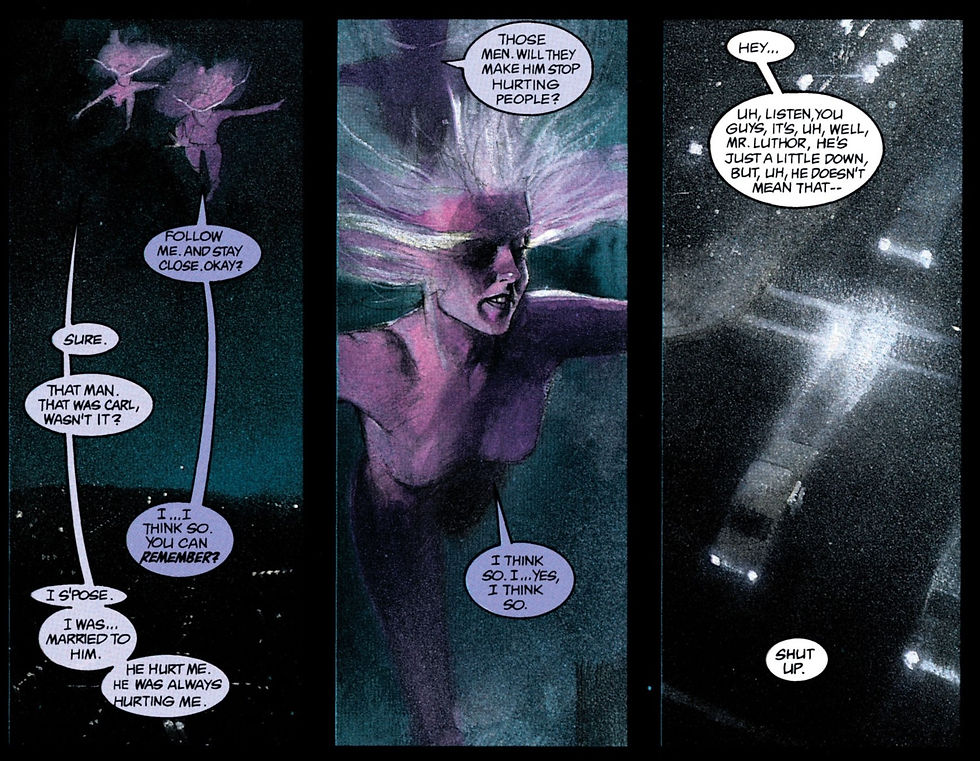

The first issue is incredibly plot-heavy, too weightily so. Gaiman reveals far too much too early, and it’s not helped by yet another storyline thrown into the mix. The organised crime gang that Black Orchid attempted to stop at the start is run by Lex Luthor. With a potential superhero involved in his operations, he needs all the help he can get keep his money safe. Almost in desperation, Luthor turns to Carl, a weapons dealer who had failed Luthor previously. By sheer luck and co-incidence, Carl was married to Susan Linden. Because he was an abusive husband, she left him and went to Phil. While Phil is the guide of the story, Carl is the antagonist, and a slightly unreliable one as Luthor later wants nothing to do with him. At the end of issue one, Carl goes after Phil for simple revenge, and it’s revealed that he was the man who killed Susan years prior. While it does add a degree of drama into the story and supplies some important moments in the second issue, Carl’s presence in the story is hard to really justify at times. The Carl-Luthor side of the tale feels heavily detached from Black Orchid’s journey, only really returning at the end. Also, I suppose this aspect of the miniseries isn’t flattering because it adds a thick layer of miserableness into the mix. With abuse and bad relationships present in the writing, it just adds to the fatigue of a first issue containing far too much plot for its own good, even if Gaiman writes a decent tale of mystery.

The second and third issues are far less plot-heavy and tend to be more enjoyable reads. Gaiman unleashes two fundamental changes into the story right at the start of the second issue. Firstly, Carl kills Phil – with that, the guide of the story is gone, and Black Orchid must begin her search for answers from others. Secondly, Carl goes into the greenhouse and kills all the remaining clones – only one escapes. Black Orchid’s two remaining clones meet and Gaiman creates a mother-daughter relationship.

While it creates a brilliant sense of loneliness in the protagonists, thereby adding to the emotional weight of Black Orchid’s quest for knowledge, Gaiman has created that relationship too late into the tale. It’s half-way through the story by the time the two Black Orchids meet, and Gaiman never develops it further or does anything interesting with it. During the second issue, the two Black Orchids go their separate ways. The younger clone gets kidnapped, but nothing interesting really comes of it since the two clones are reunited in the third issue.

Black Orchid’s search for answers is easily my favourite aspect of the miniseries, mainly because of the characters we meet along the way. Black Orchid visits Arkham Asylum – aided by Batman – to speak to Poison Ivy. After all, she was friends with Phil and Susan back in university. Although Black Orchid learns nothing new, I like Gaiman’s gritty and creepy iteration of the asylum, and we’re treated to cameos from the Joker, Two-Face, and also the Mad Hatter. I don’t know why the inmates are simply allowed to just walk around, but it is Gotham City we’re talking about.

The third issue concludes the search in Louisiana, in the swamps. There, Black Orchid finds Swamp Thing, the reincarnated version of Alec Holland (sort of). Seeing her as a kindred spirit, Swamp Thing uses his power within the Green – the energy source of Swamp Thing and other plant-powered beings – to grant her the power to create new clones. With that, Black Orchid is given new life! Although that was never the conveyed purpose of her journey, I suppose it’s a result. With Black Orchid’s journey complete, it feels like Gaiman has set the ground for an ongoing series? But what would its purpose be? That isn’t something which Gaiman goes into, especially not in the third issue. To escape from the industrial complexities of the cities, the two Black Orchids retreat to the rainforests. It’s here where they find peace, but that’s it. There have no other goals or purposes. The story becomes more directionless from here-on-out. Sure, Gaiman creates some drama by forcing a fight scene into the final pages, whereby Lex Luthor’s armed soldiers go after the Black Orchids for the purpose of both scientific research and to ensure that they don’t interfere with organised crime again. But this is where Carl returns once again. With a cache of weapons and a vengeful attitude towards Luthor for not seeing his ‘potential’, Carl attacks Luthor’s men and dies in the process. The death is written to be some kind of sacrifice, but after his murderous actions previously and his personality, it doesn’t feel like a sad moment. In the end, Luthor’s men refuse to kill the Black Orchids. They are fooled by their beauty more than their power. The Black Orchids are written to be pacifists, but they will fight Luthor if he attacks them first. Why Luthor’s goons listen to them is never really explained. I thought at first that the Black Orchids were borrowing a technique from the Poison Ivy playbook, but Gaiman doesn’t write it so. The ending feels rushed, and although the Black Orchids decide in the end that the rainforest is not for them and they wish to return to the city, that sense of directionless is still powerful.

There are some aspects which work in Black Orchid’s favour. I think the mood and style of the story is flawless. Gaiman set out to create a grim and confusing world for Black Orchid, and that sense of loneliness present throughout is exceptional. I also think that, especially during the second issue, the plotting’s natural mystery works effectively. I like Black Orchid’s quest for knowledge about herself, and I think Gaiman captures characters like Batman, Poison Ivy, and Swamp Thing very well.

Although Gaiman may transfer Black Orchid into the gritty eighties well in some ways, the miniseries lacks much excitement or originality. It’s evident from reading the miniseries that Gaiman adored Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing (vol 2), and there are many comparisons between it and this miniseries. In some respects, Black Orchid is strikingly similar to Swamp Thing, with a link to jungles and the Green. Both have an origin story full of surprises and shocks.

It’s not uncommon for writers to want to emulate Moore’s touch, and later writers like Gaiman and Morrison do enjoy their own styles. But in other ways, the miniseries just isn’t that interesting. Carl’s presence and the Luthor plot may provide some explanations to Black Orchid’s origin story, but it’s a pretty typical story of abuse and betrayal.

A huge gapping problem with Black Orchid must come from the style of its writer. Neil Gaiman, while obviously full of ideas, can barely contain himself. With all the plotting of the first issue and the lack of it in the following two chapters, the pacing of the tale is far from smooth. But on a more tiresome note, it appears that the writer is so obviously attempting to display how clever he is that the scripting is often pretentious. This isn’t just clear from some of the dialogue or the detail within panels (which, as an admirer of Alan Moore, you can be certain that Gaiman provided expansively verbose panel breakdowns to McKean), but also in the plotting during the first issue. He tries desperately hard with vigour that the plot becomes a confused mess on occasions. Sometimes, Gaiman seems to think that the clone who died in the explosion at the start was the real Susan Linden. Phil seems to fall for that as well. The same applies for Black Orchid’s main clone and her inner thoughts. Sometimes, Susan is her sister. Sometimes, Susan is her mother. Surely, as a clone, Susan is all of the Black Orchids? It’s this confusion and Gaiman’s tendency to overstate every detail of plot that can make this miniseries a challenging read at times.

A large aspect of Black Orchid’s reputation comes down to its art, or to use the more appropriate and therefore more pretentious word, illustrations. Dave McKean certainly conveys a style which, even today, is not common in the comic book medium. His art is incredibly identifiable, despite its lack of vivid colours. But to me, McKean’s art contains two problems. First of all, it’s rarely at all clear what McKean is depicting in his pages and panels. That lack of clarity damns a story to more confusions. A lack of clarity adds gasoline to the all-consuming fire of the second problem – McKean is no storyteller. McKean simply provides illustrations to Gaiman’s captions and dialogue, but never adds drama or anything of substance with his visuals. It simply doesn’t feel like a comic book, where when the medium is at its best, a powerful story is translated powerfully by an artist. At times, this miniseries can feel like an overly verbose piece of prose, one where the art serves little purpose. Out of all the scenes, it’s clear that McKean enjoyed painting the scenes in Arkham Asylum. Perhaps his talent for the grim lighting evidenced in these scenes led to him working alongside Grant Morrison on Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, published later in 1989. There, the misty and grey style of McKean works in Morrison’s favour, but less so here with Gaiman.

VERDICT

Overall, Black Orchid really is an average miniseries that isn’t the most memorable story you could read. Gaiman does update the concept well enough for a new era, but after a plot-heavy start, the tale becomes somewhat directionless and many of the characters fail to endear or entertain. I believe that Gaiman’s pretentiousness and wanting of an audience who lap up his clever storytelling often spoil what could have been a more intriguing tale. Were the story to enjoy better plotting and pacing, then perhaps Black Orchid would be more fondly remembered.

Next Week: Batman: Nightmares (Batman 516-519, 521-524). Written by Doug Moench with art by Kelley Jones and John Beatty.

Comments