POST 240 --- GREEN LANTERN/GREEN ARROW: SNOWBIRDS DON'T FLY

- Scott Cresswell

- Oct 8, 2023

- 14 min read

So, after one year at the helm, Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams had transformed Green Lantern (vol 2) from an aged Silver Age comic into a visionary Bronze Age title to shape the medium for decades to come. The creative team, using Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and Black Canary like pieces on a chessboard, had painted a picture of America that was more realistic grimness than fantasy. O’Neil’s focus on race, the environment, and overpopulation, marked the start of a new kind of plotting and storytelling. O’Neil was to continue in that direction for another year – naturally alongside the talent of Neal Adams – and deliver several more ground-breaking tales, one of which went to the heart of the dark side of American youth culture…

Green Lantern (vol 2) 83-87, and 89 was published from May 1971 to April 1972. With issue 89, the title was cancelled. It did return, but it took four years. The original story of Green Lantern (vol 2) 90 had already been completed, and it was released in The Flash (vol 1) 217-219, published from September 1972 to January 1973. Like before, the stories were written by Dennis O’Neil with the art by Neal Adams and a number of inkers.

And A Child Shall Destroy Them --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

While the last issue of the previous batch of Green Lantern/Green Arrow tales provided an unwelcome return of hard fantasy (Green Lantern (vol 2) 82), Green Lantern (vol 2) 83 returns us softly to that classic mixture of realistic themes with a fantastical element in the plot. O’Neil focuses on Sybil, a little girl with bizarre psychic powers. At the start of the story, she cripples a helpless Carol Ferris on the order of a grumpy old man. Carol Ferris – who sometimes transforms into the villainess Star Sapphire – is a love interest of Hal Jordan’s, but she doesn’t know he is Green Lantern – yet at least. It turns out that Ferris’s fiancé works at Meadowhill School, where Sybil is used and abused by the adults, one of whom is Grandy the Cook. In yet another coincidence, it’s at this school where Black Canary – as Dinah Lance – is hired to work. While O’Neil does certainly go overboard with the cliched coincidences, the theme here is abuse. Sybil is abused by Grandy the Cook, who takes advantage of her powers. According to Dick Giordano, the physical influence for both Sybil and Grandy is US President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew respectively. It’s common knowledge that O’Neil and Adams – clearly not Republicans (perhaps to the point where some rightists would disregard them as ‘commies’) – are not at all fans of the government of the time. But, in keeping with the political and public perception of the time, Agnew (or, in this case, Grandy), is considered the darker force of the two when compared to Nixon (Sybil). That parallel may fall flat for O’Neil and Adams, especially since in this story, Sybil really is blameless and only wants to be a normal child and no longer wants the abuse. Green Lantern and Green Arrow hear of the school’s reputation from both Ferris and Black Canary, but in the end, Sybil fights back and destroys the building. O’Neil’s writing about a serious topic like abuse is improved with the use of contemporary political references, fantasy, and a creative light-touch which he always brings to his stories. O’Neil doesn’t go too far in over-egging scenes of violence and abuse, allowing the subtle dialogue and startling art do its job. Overall, O’Neil writes a great story for Green Lantern (vol 2) 83, and he somehow succeeds in giving Hal Jordan more of a personality when he is reunited with Carol Ferris.

Peril In Plastic --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Bernie Wrightson

Green Lantern (vol 2) 84 continues the saga of Carol Ferris and her disability. Looking to recover the use of her legs, Ferris accepts an invitation from the Mayor of Piper’s Dell, a mysterious town. Green Lantern and Green Arrow think nothing of it until they hear that a terrorist attack is taking place in that same town. It turns out the mayor of this town is none other than Black Hand. He – alongside Sinestro in the previous issue but one – are the only two traditional Green Lantern foes to turn up in the O’Neil/Adams run. Carol Ferris’s invitation was a simple ruse so he could trap and kill Green Lantern – Black Hand used plastic-creating factories to control the townspeople. Naturally, the heroes put an end to Black Hand’s plans, making this story appear to be one of the more generic and pedestrian tales of the run thus far. As you’d expect, O’Neil does add an ethical issue into the mix with plastic. This isn’t conveyed just with Black Hand’s plastic plans, but also at the end when our heroes go Christmas shopping, and Oliver Queen doesn’t disguise his environmentalist and moralist criticism of plastic Christmas trees. It’s another sign of O’Neil’s writing looking further ahead than many of the politicians did, but sadly it leaves very little impression on the reader. The focus on plastic – while welcome and interesting – is buried under a pretty dull plot with a bland villain. Overall, it’s clear that Dennis O’Neil had higher hopes for Green Lantern (vol 2) 84.

Snowbird Don’t Fly/They Say It’ll Kill Me… But They Won’t Say When --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

Without much of a doubt, it’s Green Lantern (vol 2) 85-86 which fans remember the O’Neil/Adams run for the most. The focus on drugs and addiction seems a more advanced topic compared with the environment, plastic, and even race – let alone the typical outer-space invasions Green Lantern faces. Why are drugs the most shocking focus of the run? It’s partly to do with a younger audience present, but also because the 1970s were an era where drug-taking and addiction grabbed sizable numbers of youths. It was considered such a large-scale issue that, on 18th June 1971, Nixon declared a “war on drugs” and that they had become “public enemy number one.” With the federal government taking drugs more seriously and attempting to tackle the situation with the use of legislation, O’Neil and Adams placed themselves in a position more understanding of drug-users and addiction.

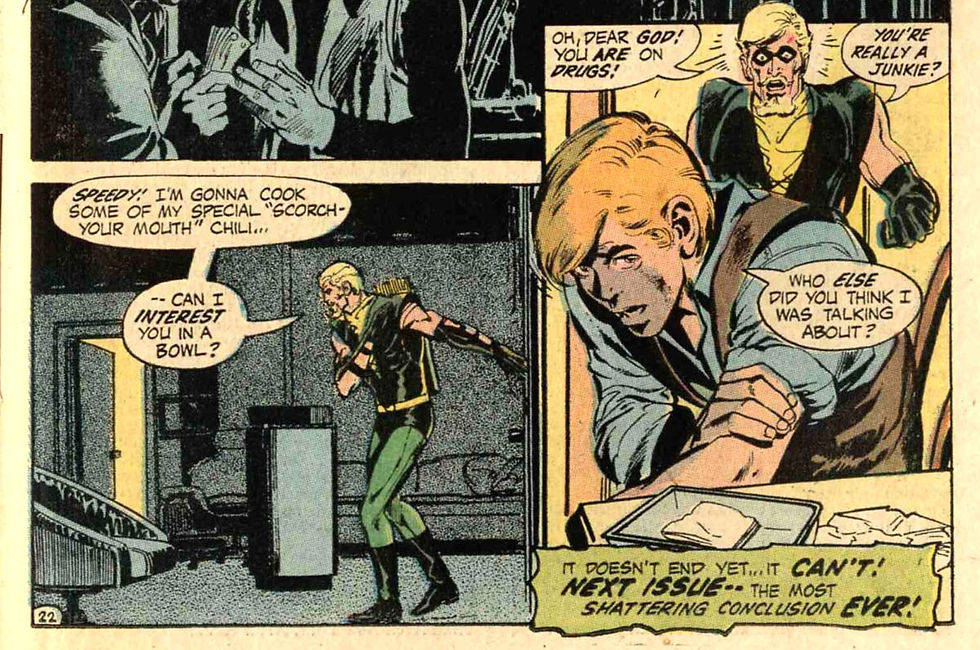

Green Lantern (vol 2) 85 begins with a shooting, specially of Green Arrow. Shot by one of his own arrows, Green Arrow worries that his ward Roy Harper – better known as Speedy – has been kidnapped. In a scene which DC certainly would never have published before 1970, O’Neil displays a junkie begging for drugs from the local dealer. Although that is something which readers of today may be used to, when you reader the kind of climate of comics in the Silver Age, the existence of such a scene has a huge impact. Green Arrow follows the trail of the dealer only to find Roy in the drug den. Green Arrow is delighted to find his sidekick seemingly using his own initiative to take out the baddies. But before Roy Harper can even reveal a sprinkling of the hard-truth, Green Arrow and Green Lantern go after the dealer. In yet another shocking scene, the villains try to get the heroes imprisoned by poisoning them with drugs. The villains partially succeed. It’s strange witnessing Green Lantern and Green Arrow both absolutely out of it on the hard stuff. But again, it’s a sign of Dennis O’Neil taking worthwhile risks as a writer. It’s Roy Harper who saves both the heroes from the police finding them, but that is when the story’s first part ends with the biggest gut-punch of the run.

Green Lantern (vol 2) 86 starts with a death. One of Roy’s drug-addicted friends takes an overdose and dies. These cold words are translated masterfully by Neal Adams’s sense of art and storytelling, transforming such a shocking scene from an idea into a moment, one which really shows how comics can be a powerful medium used to address the most serious of issues and questions. This issue may focus more on Speedy, and that is right, but the death of the drug addict and the sheer shock-value of such a moment shouldn’t be forgotten. While Green Arrow and Green Lantern put an end to the drug-trafficking, it will take much more than that to fix the relationship between Oliver Queen and Speedy. This is where addiction, loneliness, and neglect become the themes of the work. Speedy – like many other young people – sees drugs as an escape, an exit from his unnatural life as a superhero. Oliver Queen – still being, in some ways, the arrogant and hard-headed figure that he was before was left on that desert island – is no father figure. He is simply reckless as he took little responsibility for Roy Harper when he was a child. That negligence and the turn towards a darker lifestyle makes O’Neil’s transformation of Green Arrow away from a simple Batman clone complete. With Speedy no longer a tiresome Robin duplicate, O’Neil has made Speedy into a fantastic character with so much depth. While O’Neil doesn’t end Green Lantern (vol 2 86 on a completely sour note, as Speedy does rescind his addiction, that once-strong relationship between father and son is broken (they aren’t biological family, but the point stands).

Overall, this two-parter leaves an impression because its focus on drugs is so broad. O’Neil does more than simply paint the immediate outer body ‘enjoyable’ experience of drugs, and its negative effects upon society. But he also depicts how drugs destroy people, their families, and their relationships. The story was impressive enough that, at the start of Green Lantern (vol 2) 86, there features a letter from Mayor of New York John Lindsay no less. DC made much of it on the cover of the issue, but upon reading the letter, Lindsay – or probably more accurately his staff – make no mention of O’Neil’s story. It’s frankly a talk down to readers about the horrors of drugs and why they are bad. While the content of the letter may be – to put it mildly – unimpressive, the fact that DC were recognised for focusing on such a relevant issue was a sign that, for the first time in such a long while, they were finally moving with the times…

Beware My Power --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

Green Lantern (vol 2) 87 was – for some strange reason – split into two. One story features Green Lantern, while the other Green Arrow. But like the previous two issues, this one has become another fan favourite, and that’s because it features the debut of a new Green Lantern! One day in California, Hal Jordan discovers that his ally, Guy Gardner, has been badly injured rescuing a helpless child. Because of his injury, the Guardians decide that they must appoint another Green Lantern. With Hal Jordan’s help and advice, they choose John Stewart, a black man living in the ghettos who stands up to the police. With the O’Neil/Adams run nearing its conclusion, here it feels like things have come full circle. In Green Lantern (vol 2) 76, Hal Jordan recognised his failings when it came to standing up for the socially oppressed on Earth, and with this issue, a new Green Lantern from the trodden on and looked down upon has risen in John Stewart. Thankfully, unlike Hal Jordan, Jonh Stewart does have a personality. He is hard-headed, streetwise, and has an attitude, but his morals and ethical beliefs make him a suitable Green Lantern in the eyes of the Guardians. Hal Jordan – at first – isn’t convinced, and it takes until the end of the story for our usual Green Lantern to realise that perhaps the Guardians have learned something worthwhile from the adventures around America enjoyed by one of their own (Old Timer from Green Lantern (vol 2) 76 to 81). All-in-all, O’Neil writes a fairly basic tale for John Stewart’s debut, but that certainly works in its favour. This is a showcase of new personalities and a new kind of Green Lantern, one more adapted and suitable for the dawning Bronze Age…

What Can One Man Do --- Written by Elliot S. Maggin with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

Compared to Green Lantern’s half of Green Lantern (vol 2) 87, Green Arrow’s segment is perhaps less memorable. But it still nonetheless leaves an impact. Written by Elliot S. Maggin – not usually a writer who I’d associate much quality to – we’re treated to a story where Oliver Queen’s depression and angst about the problems of America make him a potential candidate for political office. As Green Arrow, he witnesses the terrible crimes on the streets and here, Maggin writes an emotional kind of tale involving Oliver Queen and a young orphan on the streets, who is shot and killed. With subtle dialogue and captions throughout – once again surprisingly by Maggin and not by the likes of O’Neil – Green Arrow takes the orphan to a hospital, but it is too late. The raw emotion of Green Arrow witnessing such tragedy and terror is what leads him to decide that he must run for Mayor, thus beginning the long saga of Oliver Queen’s political ambitions. In many of the stories of today, we’re so used to tales of street violence and then witnessing the masks of superheroes slip as their human side appears so briefly. But back in the early-1970s, tales of this calibre felt new, and more to the point, they felt more powerful. Maggin’s excellent scripting and Adams’s brilliant storytelling adds a layer of drama that grows heavy as events progress. Throughout the run, Green Arrow has been very emotional, but not like this. He’s been severely angry and displeased with business, criminals, and others who abuse those below them, but here we watch as a superhero sheds a tear…

And Through Him, Save a World --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

Green Lantern (vol 2) 89 was not meant to be the end. While the previous issue (88) was a reprint of old tales where the Green Lantern of Earth-2 met his Earth-1 counterpart, it was to be four years later when Green Lantern (vol 2) 90 arrived on the shelves. Therefore, this is the final tale in O’Neil/Adams run, at least in the mainstream title. Here, O’Neil focuses on an aspect which – fifty years on – has enjoyed something of a resurgence - eco activism. The story focuses on Issac, an activist who has covered the offices of Ferris Aircraft’s buildings with sewage and waste. Naturally, Oliver Queen is amused and supportive of this, while Hal Jordan less so. The heroes investigate the case, finding that Carol Ferris’s company is creating a new source of energy which could damage the environment. Meanwhile, Issac is revealed to be a former scientist who began activism after he discovered that pollution has committed serious damage to his lungs. The focus here is just how far Issac is willing go for his aims. For instance, he damages one of the machines in the factory which collapses and nearly kills Carol Ferris. Issac has become so obsessed in his goal that he no longer thinks about the effects of his actions on other people. In the end, Green Lantern and Green Arrow are captured by security, mainly because the latter supports Issac. But meanwhile, Issac has crucified himself on the front of a test plane. Even though this will kill Issac – and it does – because of his health, the fact that Issac is willing to put his life aside and fight for his important cause convinces Green Lantern. In the end, Green Arrow remains as supportive of Issac’s cause, and Green Lantern nonchalantly destroys one of Ferris’s ultra expensive aircrafts for the damage it does to the environment. Compared to other stories in the run, this feels slower and takes a while to – excuse the pun – get off the ground. That may be because of the exposition and heavy use of dialogue, but O’Neil’s focus on both the environment and the ethics of protesting is a fascinating area to explore. It’s clear from the story that both O’Neil and Adams are on the side of Issac – after all, why else would they depict him crucified like Jesus Christ? But O’Neil presents us with the two sides of the story. It’s why Green Lantern spends much of the first half of the story with Carol Ferris learning about the company’s plan. But O’Neil marking a shift in Hal Jordan’s belief makes for an interesting ending, one which proves that this story has left an impact on the Emerald Knight.

The Killing Of An Archer/Green Arrow Is Dead/The Fate Of The Archer --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

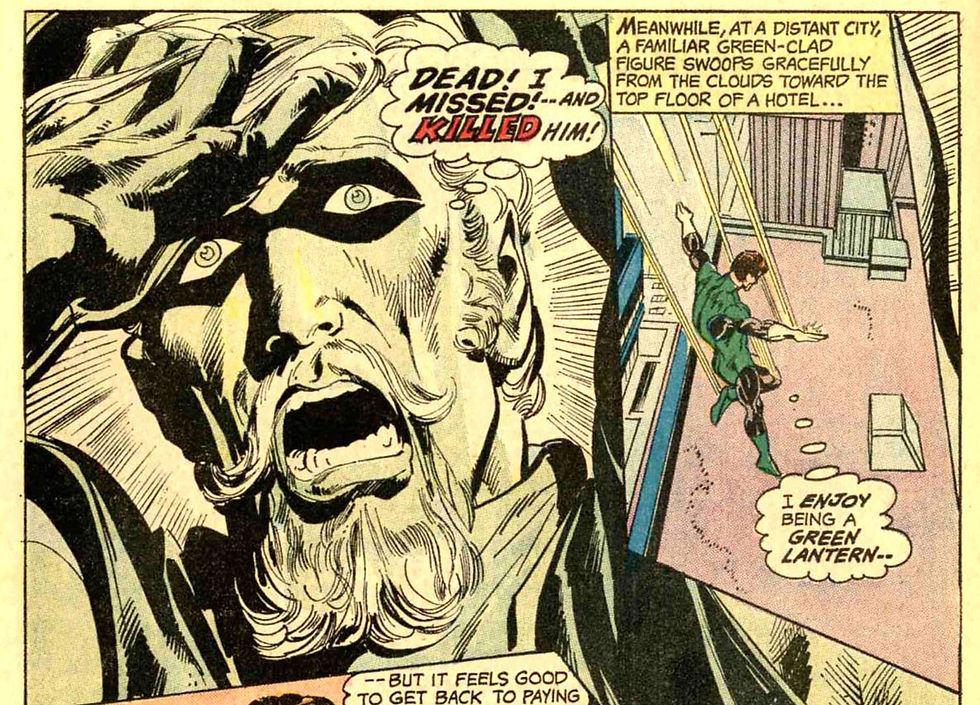

The Flash (vol 1) 217-219 presented readers with short back-up stories, all of which were meant to be the original Green Lantern (vol 2) 90. And if only it were, for O’Neil pens another tale which leaves a lasting impact. In the back alleys, Green Arrow is blinded by a group of criminals. With his vision altered and his aim badly-off, Green Arrow shoots his bow at one of his attackers, only for the arrow to bury itself in the criminal’s heart and kill him. Cue yet another dramatic Neal Adams panel!

Ashamed of himself, Oliver gives up being Green Arrow and escapes from the city. Green Lantern and Black Canary go looking for him, and O’Neil pads out the story by adding in some criminals who blow up a neighbourhood block, thereby delivering some action into the plot. But it’s revealed that Green Arrow has escaped to the mountains and gone to live with some monks.

The way in which Green Arrow is brought back is both romantic and stupidly unbelievable. Black Canary is hit by a car, and she needs a blood transfusion. She has a rare blood type. Guess who has the exact same blood type as her? Yes, this is a cliched way of brining Oliver Queen back. Black Canary’s injury feels entirely random, and overall O’Neil doesn’t handle Green Arrow’s comeback well in that sense. But O’Neil brilliantly explores the psyche of Green Arrow and his guilt over his failure. This is something which Mike Grell would heavily expand upon in his monolithic Green Arrow (vol 2) run in the late-1980s and early-1990s, but this time, Green Arrow restores his faith in himself by rescuing Green Lantern from a villain with a well-placed dead accurate shot. Overall, this tale does feel disjointed due some of the subsidiary plots, and O’Neil doesn’t do himself many favours with the blood transfusion tale, but this deeper examination of Oliver Queen’s personality and the high standards he holds himself in is flawless.

O’Neil and Adams did collaborate once more in a story published in The Flash (vol 1) 226. Entitled The Powerless Power Ring, this story was released in April 1974 and was only eight pages long. It’s pretty much just Hal Jordan chilling in a forest, enjoying Oliver Queen’s recipe of chilli and mushrooms before, suddenly, his ring loses its powers. Green Lantern manages to recover the power of his ring just in time to rescue a rock-climber. It’s revealed at the end that it was the mushrooms which caused Green Lantern to lose his powers. It’s a short little tale by O’Neil and it certainly looks pretty with Adams and Giordano present. It’s hard to either criticise it or praise it. There’s little of substance or importance in it really. Green Arrow doesn’t turn up once – it’s just a peek into the kind of mundane life Green Lantern might usually live. When you realise that the only point of interest in the story is the mushrooms, then you know the story is nothing spectacular.

Exceptional, awesome, dramatic, impressive, detailed, and theatrical. These are all suitable words to describe the work of Neal Adams in this run. Everything I said in the previous post still stands here without any shadow of a doubt. As ever, Adams does more than go with the flow of O’Neil’s radical stories. Adams adds a whole new layer of storytelling and drama which only an artist like himself could achieve, helped once again by inkers like Dick Giordano. Along the way, we’ve also witnessed covers which had left an undeniable impact on the medium. Green Lantern (vol 2) 85 comes to mind, where we as readers witness Speedy taking drugs while Green Lantern and Green Arrow watch on. Like many of the best projects in the medium, this run really has been a partnership between writer and artist. The partnership of O’Neil/Adams is like that of Wolfman/Perez or Claremont/Byrne rather than Kane/Finger or Lee/Kirby. You really do feel that O’Neil and Adams have plotted out these stories together. It is helped hugely by their similar political views and their fervent anti-Republicanism and dislike of social conservatism. But overall, it was this partnership that moved comic books into the modern age, and without the art of Neal Adams, this run could have fallen severely flat.

VERDICT

Overall, the second half of O’Neil/Adams’s Green Lantern/Green Arrow continued down the similar path of exploring aspects of life which were once no-go areas for the likes of comic books. But O’Neil goes further by involving Speedy in drugs and thereby the stories raise issues surrounding parenting, and youth culture. All-in-all, The O’Neil/Adams era of Green Lantern (vol 2) just prove how much more in touch these two creators were compared to others at DC. What has certainly helped O’Neil and Adams is that five decades on, many of the issues discussed here are still relevant. Although both creators passed away (O’Neil in 2020, Adams in 2022) perhaps saddened by the slow movement of progress surrounding many of these issues, the fact that this run is remembered and considered such a giant today is proof that O’Neil and Adams will stand tall as two classic giants of such a crucial medium of storytelling.

Next Week: Batman/Dark Joker: The Wild. Written by Doug Moench with art by Kelley Jones and John Beatty.

Comments