POST 239 --- GREEN LANTERN/GREEN ARROW: HARD-TRAVELLING HEROES

- Scott Cresswell

- Oct 1, 2023

- 15 min read

What are some of the most important comic books ever published? Obviously, the list is highly extensive. But perhaps two well-deserving qualifiers would be 1959’s Showcase 22, and 1970’s Green Lantern 76. The creation of Hal Jordan by John Broome and Gil Kane in Showcase 22 launched DC’s Silver Age – a period when superheroes returned to the spotlight and reinvigorated the world of comics with tales of science-fiction, fantasy, and outer-space adventure. Green Lantern – along with the Flash, the Atom, Hawkman, and of course the Justice League of America – defined DC Comics during the sixties. But in 1970, it was time for another era. The likes of Fox and Broome had been penning tales for decades, and new creators with fresh ideas and perspectives were needed. Up until the start of the seventies, Green Lantern (vol 2) had been dominated by Hal Jordan facing alien threats, heading into space, and working blindly to the commands of the Green Lantern Corps and the Guardians of Oa. But with Green Lantern (vol 2) 76, a more adult and serious world was unleashed. Mainly to increase the sales of the title, Green Lantern was joined by a revamped and rougher Green Arrow. The arrival of Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams as writer and artist respectively planted the seeds of more realistic and urban storytelling which grew to dominate the medium in the seventies, the eighties, the nineties and beyond. Green Lantern (vol 2) 76 is when the world grew darker. This is when the Bronze Age began…

The O’Neil/Adams run of Green Lantern (vol 2) – or more commonly known as Green Lantern/Green Arrow – is incredibly famous and highly-regarded. I want to explore what it was successful and compare it both to the comics that preceded it and succeeded it. Here, I’ll be looking at Green Lantern (vol 2) 76-82, published from April 1970 to March 1971. Written by Dennis O’Neil and pencilled by Neal Adams, several inkers were involved, most notably Dick Giordano.

No Evil Shall Escape My Sight --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Frank Giacoia

The issues of Green Lantern (vol 2) preceding issue 76 were still being plotted and written by John Broome. His sci-fi and fantasy approach to the title had had its heyday of success, but by 1970 it appeared old. Hal Jordan’s Green Lantern was always heading out into space or fighting threats unknown to man. Jordan may have been a man of impeccable morals, but underneath his appearance of a test pilot, he was terribly dull. So, Green Lantern (vol 2) displayed a typical world for superheroes, one where the goodies were nothing but good, and the villains were comically evil. In 1970, that all changed.

Green Lantern (vol 2) starts like many other Green Lantern stories, at least in terms of the story (but certainly not in terms of the artwork!). Green Lantern flies above Star City and breaks up a fight between a tenant and his landlord. At first sight, this is Green Lantern just doing his job. But then the other tenants in the block begin to pelt Green Lantern and the landlord with rubbish. This is where Green Arrow enters the scene. Although completely redesigned by O’Neil to be no longer be a simple Robin Hood lookalike, those morals of that legendary figure are now fully infused within Oliver Queen as Green Arrow. He argues with Green Lantern for standing up for the landlord. Green Arrow shows Green Lantern the condition of the housing, and the emerald knight learns that the rich landlord doesn’t just refuse to pay for repairs, but that he will soon be booting out all the poor tenants. O’Neil raises that ancient and politically charged question about whether to side with the landlord, or the tenant. But O’Neil uses this situation to display Green Lantern’s confused state of mind and morals. It’s all exemplified flawlessly with a scene where Green Lantern is met with a poor black tenant:

This is undeniably one of the most memorable moments in the whole run. But it’s undoubtedly the most important. O’Neil doesn’t just raise moral and racial questions which regular Americans and people across the world were grappling with, but he harnesses reality to completely transform Green Lantern’s view of himself. That idealistic world created by Fox and Broome is worthless now. Green Lantern must face up to reality. By working alongside Green Arrow, Green Lantern manages to reveal the landlord’s crimes to the world, and he is arrested. O’Neil may change Green Lantern’s perception, but he doesn’t leave one rose-filled paradise to simply find himself firmly planted elsewhere. Like all human beings, Hal Jordan is conflicted with himself over certain aspects. He begins to doubt the Guardians of Oa, who seem completely unaware of the racial and social problems of a meagre planet like Earth. For too long now, Green Lantern has protected Earth from alien threats, when perhaps the larger and more severe threats are in the homes, on the streets, and in the cities of the world. In this story, Green Arrow is a conduit for this perspective, a new view not just to the emerald knight, but also to many readers of comics in 1970. O’Neil doesn’t need to create a new structure for the rest of the story – Green Lantern finds the threat and puts him to an end. But that flawless rollercoaster journey and the crumbling of an old-world order signifies a huge change in the title. Faultlessly, Green Lantern (vol 2) 76 begins a new era.

Journey To Desolation --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Frank Giacoia

For the first few issues of the Green Lantern/Green Arrow series, the heroes are joined by one of the Guardians of Oa. Nicknamed Old Timer, this Guardian is dispatched to learn more about the divisions of society after they show confusion and distaste for Hal Jordan’s change of heart. Green Arrow attempts to convince the Guardians that they must understand the areas of the universe they swear to protect. Therefore, Old Timer tags along and makes for a great companion.

O’Neil’s personal politics may – even in today’s climate – appear modest. But in 1970, the United States was still on the long path of recovery after the bloodbath of Vietnam, the chaos of the Democratic National Convention two years prior, and the tragic assassins of Martin Luther King Jr and Robert Kennedy still fresh in the minds of all. O’Neil taps into the nation’s distress and that feeling is exuded by Green Arrow. An idealist with a gruff tone, Oliver Queen is a reactionary hero who – in theory – should never be paired with a dully conservative-type like Hal Jordan. But that’s where the surprising – but shockingly believable – friendship between the two heroes grows from. Oliver Queen sees the good in Hal Jordan’s morals, but strongly believes that they should be targeted on social ills. Therefore, Green Arrow, Green Lantern, and Old Timer go on a road trip through America in search of its true face. Such an approach to plotting – especially in a comic book – is completely unexpected, but it does work astonishingly well. It’s partly down to O’Neil’s strongly held views, but also because unlike other creators, he understands the youth culture and troubles of the United States at that time. Green Lantern (vol 2) 77 is a prime example of this, as the travelling trio come across Desolation, a mining town where the workers are forced down the pits while the coal baron sits back with his riches controlling and manipulating the town.

Its plot may seem somewhat like the one explored in the previous issue. If anything, it goes a tad further. Slapper Soames (excuse the pretty laughable name) is not only in control of the town, but he holds the leader of the revolutionary miners in prison. The miners treat their leader like a saint. It’s difficult to surmise whether O’Neil was intentional in aiming for this, but it feels like the situations, contemporary at the time, occurring across the world, most notably in South Africa where Nelson Mandela was kept behind bars by a white-only establishment. Of course, O’Neil doesn’t just reproduce a tacky carbon copy, but once again, it’s that awareness and ability to carefully and successfully adapt the grim and gritty reality into the world of comic books. We all know that Green Lantern and Green Arrow will win in the end, but overall Green Lantern (vol 2) 77 intentionally depicts America at its worst, whereby the bosses trample all over the workers. It’s something which the likes of DC had never explored before…

A Kind of Loving, A Way of Death --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Frank Giacoia

Green Lantern (vol 2) 78 throws – alongside the usual emerald duo – another DC hero into the mix. Black Canary became a member of the Justice League of America during O’Neil’s run during the late-1960s, and that is when her romance with Green Arrow blossomed. Thankfully, O’Neil doesn’t dive into the detail of her background on Earth-2. Instead, she only plays a significant role in the tale towards the end. Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and Old Timer arrive in a small Native American reserve. There, a group of white racist bikers attack a native, and the heroes come to the rescue. Modern comics spend much of their time focusing on racial issues and discrimination, but back in 1970, it was a subject rarely touched or focused upon. Discrimination isn’t – however – the only focus of this story. O’Neil adds a degree of fantasy to this plot with the introduction of Joshua. This weapons-master has brainwashed Black Canary in his deranged goal to take up arms to kill all the non-whites. O’Neil’s mixture of reality and fantasy is subtly executed here with effectiveness. And it’s aided by the closeness of Green Arrow’s relationship with Black Canary. It all comes to a head when Joshua orders Black Canary to kill Green Arrow. O’Neil builds up the tension slowly, helped significantly by Neal Adams’s dynamism. Black Canary refuses, and Green Lantern arrives just in time to take out Joshua. This being a significant event, O’Neil writes this scene to be a memorable one for Black Canary. Even though she was brainwashed, she feels intense guilt for nearly killing her lover. When you bear in mind that back even in the Bronze Age, characters seemed to have a memory of just one issue and nothing more, O’Neil’s formulation of a character-arch is excellent. That said, the tension between Green Lantern and Green Arrow does seem to have paused immediately. That feeling of anxious drama between the conflicting approaches of the two emerald heroes seems sadly missing, especially after Green Arrow calls Green Lantern his best friend here. Of course, drama does return, but it does seem like the personal development of Green Lantern’s journey has been thrown to the side, despite the high quality of such a story like this one.

Ulysses Star Is Still Alive --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dan Adkins

Green Lantern (vol 2) 79 continues focusing on discrimination against Native Americans. Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and Old Timer come across a group of white locals attempting to execute a Native American. Naturally, the heroes intervene, and they learn that both sides are involved in a dispute about who owns the nearby land. The Native Americans want to keep their previously negotiated deal with the government that they can keep their reservation, while the white businessmen believe they have ownership of the trees. O’Neil evolves the story from a land argument into one of deliberate sabotage, whereby the records conveying the original land deeds are burned. It’s all part of a plot to take land from the Native Americans. As ever, it’s clear who O’Neil is gunning for, and those views are obviously espoused by Green Arrow. Once again, it’s a strong example of O’Neil harnessing both history and relevant social issues in America to paint a more accurate, and therefore a more negative, picture of the country. Where the story falls flat and even enters the territory of unbelievably silly comes with Green Arrow. To provide enthusiasm and support to the Native Americans, Green Arrow disguises himself as Ulysses Star, the original leader of their tribe. Were such an idea mooted in the Silver Age, then I’d be unable to take issue with it. But since O’Neil has cultivated an issue with a realistic plot with little room for laughs, Green Arrow’s comic performance as the ghost of a Native American is just bizarre and plainly odd. That considered, it does create a much-wanted degree of drama between Green Lantern and Green Arrow, with the former wanting to create some peace, while the latter is with the natives all the way. Overall, Green Lantern (vol 2) 79 does deserve recognition for its boldly realistic plot, but I have to say that is why I fail to really enjoy this tale. O’Neil focuses far too much on land rights and deeds rather than sabotage and the rights of people. The multiple themes could have been blended better, but as it stands, this issue doesn’t shine too brightly due to exposition and its uneventfulness.

Even An Immortal Can Die --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams, Dick Giordano, and Mike Peppe

Green Lantern (vol 2) 80 begins a solidly rewarding two issues in the O’Neil/Adams saga. The spotlight is – finally – on Old Timer. I haven’t really discussed this Guardian of Oa much at all. While he scarcely features much at all in most scenes, it would be unfair and incorrect to suggest that he adds nothing of value. Although an immortal and an alien of much knowledge, Old Timer lacks any experience of Earth and its people. Throughout the run, he slowly leaves his conservative shell and witnesses not just the worst of humanity, but also its best. For instance, in Green Lantern (vol 2) 77, there’s a great scene where he saves one of Desolation’s children lost in the fog of conflict. Old Timer begins to expand his view outwards, and that is something which the Guardians of Oa frown upon.

Upon entering a city, the heroic trio come across an overheating cargo ship. Green Lantern is knocked unconscious while trying to rescue the crew, leaving Old Timer to revive him and Green Arrow to throw off hazardous barrels of poison and waste into the river to avoid further destruction. After abandoning ship, a voice comes from the sky directed at Old Timer. His own Guardians of Oa accuse him disregarding others to save Hal Jordan’s life, and then committing further crimes against humanity by throwing the barrels into the water.

As ever, O’Neil places the moral and relevant questions first. The environment was an issue that most political leaders would not even acknowledge or accept as an issue of importance until the later years of the century. As is common, popular culture and literature being decades ahead of politicians and leaders.

Sadly – like the sinking ship – O’Neil abandons the focus on the environment. Instead, Old Timer is forced to follow the words of his Guardians and return to their planet for trial. However, Green Lantern (vol 2) 80 depicts a detour. The heroic trio are transported to a mysterious planet where the legal system has been manipulated by a masterful mechanic, who is holding the usual judges and jurors in prison. Typically, Green Lantern and Green Arrow save the day, but overall, this issue isn’t a great one. It’s average and pedestrian in its plotting, but it does hint at an interesting future for Old Timer…

Death Be My Destiny --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano

Now on trial for real at the hands of the Guardians of Oa, Old Timer pleads guilty to the charge that he jeopardised the future of the Earth. Green Lantern and Green Arrow, along with Black Canary, try to convince the Guardians otherwise, but to no success. Old Timer’s immortality is taken from him, and he is forced into exile. This is where the volcano of growing dissent and anger explodes from Green Lantern. Events during the run have caused him to doubt his famous pledge of “In brightest day, in blackest night, no evil shall escape my sight, let those who worship evil’s might, beware my power, Green Lantern’s light.” It’s not that Hal Jordan is no longer good, but that he thinks the Guardians represent too outdated and therefore unhelpful morals and beliefs. At the start of the run, his conservatism would have allowed him to subscribe to that pledge without a second thought. Now, thanks to O’Neil’s reconstruction of Hal Jordan, there has been a fascinating and groundbreaking change in a title and hero which seemed for so long to be so stuck in its old ways.

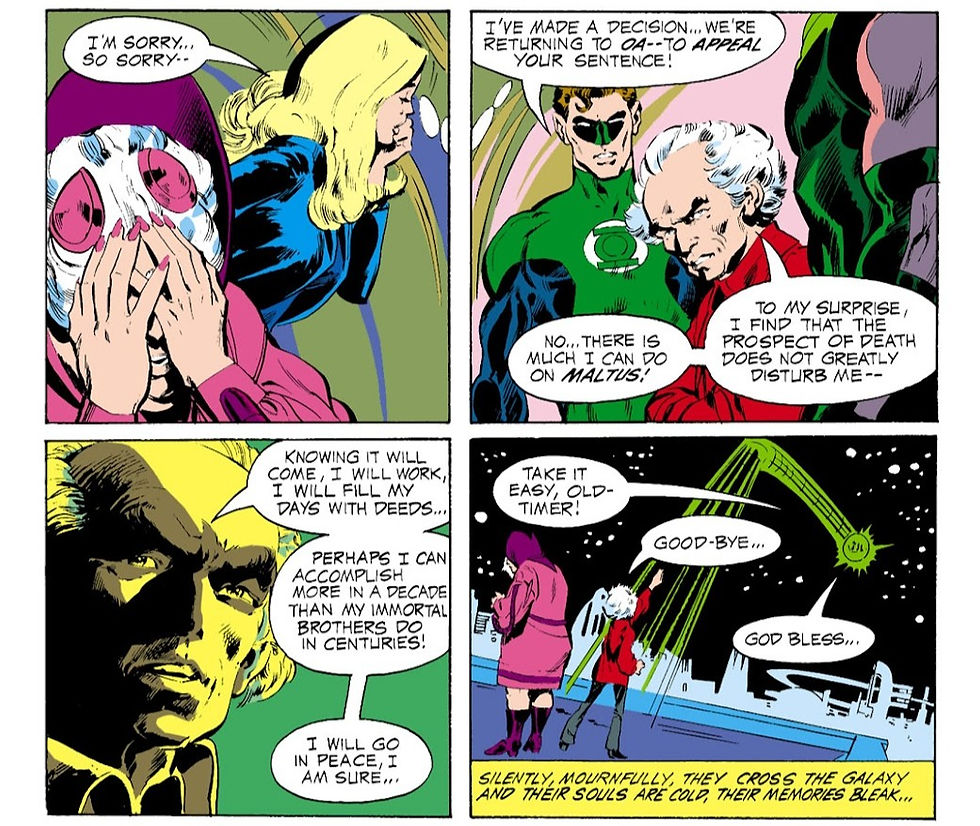

Green Lantern (vol 2) 81 takes us to Maltus, where Old Timer has been condemned in exile. Tagging along with him to say goodbye, Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and Black Canary notice the huge overpopulation of the planet. The civilians are not pleased at meeting the outsiders, but they quickly come to despise Black Canary. It’s revealed that due to some hazy and hugely underwhelming events surrounding astrology, Maltus is overpopulated, and the people now hate outsiders who come to stay, and women who can bear children. A leader named Mother Juna is seemingly behind the planet’s problems, and the heroes go for her and her goons. Although painted as an evil villainess, O’Neil reveals at the end that she is unable to have children and she began cloning people to create life and become a mother. It’s impossible to ignore the gaping plot holes and unrealism here. Did Mother Juna want hundreds of children? If not, then how did the planet become so populated? O’Neil ends the story painting Mother Juna as misguided, but not evil. That’s not a bad ending, but she isn’t one of O’Neil’s most gripping or even most interesting villains. The concept of the story is brilliant however, and it raises the moral and ethical questions which O’Neil has explored so exceptionally. It also makes for a solid, but naturally sad, farewell to Old Timer. He says behind to guide Maltus and its future. Although used sparingly, Old Timer is an unforgettable addition to O’Neil’s run, and now his mission to explore humanity and the emotional complexity of the universe is complete…

How Do You Fight A Nightmare? --- Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams, Dick Giordano, and Bernie Wrightson

In the previous issue, O’Neil concluded the successful road trip of Green Lantern and Green Arrow. But that certainly isn’t where the run ends. O’Neil continues to pen exceptional and moralising tales, but Green Lantern (vol 2) 82 feels like a return to the past. One day Green Arrow visits Black Canary with a gift. But suddenly, that gift explodes, and two winged monsters appear. Green Lantern investigates this supernatural occurrence and finds its source in the Witch Queen. With her pink-jewelled sceptre, the Witch Queen traps Green Lantern in another realm. O’Neil returning Green Lantern (vol 2) back to fantasy seems odd after the last half-a-dozen issues. While the quality of dialogue may have improved from the days of Fox and Broome, the plotting here is worse. O’Neil dives far too deep for my liking into myths, legends, and fantasy. Green Arrow and Black Canary locate a group of Amazons, whose hatred of man goes back to some magical wizard who trapped them in the same dimension as the Witch Queen. To me, this is all frightfully dull stuff, but O’Neil does add a cushion of familiarity into the fray when Sinestro is revealed as one of the villains. He is an ally of the Witch Queen, but when Black Canary and Green Arrow team-up, the foes are beaten. In the end, Black Canary heads into the world of the Witch Queen and rescues Geren Lantern. In terms of plotting, it is like something from the height of the Silver Age. I suppose, were this story surrounded by the kind of tales that Broome would write, and Kane would pencil, then it would appear much greater than it is. O’Neil’s more modern way of storytelling, combined with Adams’s art, makes the tale look stunning. But when you compare it to the realism and moral focuses of O’Neil’s writing up until this point, Green Lantern (vol 2) 82 appears silly, boring, and not particularly entertaining. It doesn’t help how fantasy stories of their calibre aren’t personally interesting, but overall, this is poor compared to the thrills of previous plots and subsequent stories.

While it is the writing of Dennis O’Neil and his own views and perspectives that have shaped the plots, characters, and fantastic moments throughout Green Lantern (vol 2) 76-82, Neal Adams has been more than a plain artist or storyteller. With such realism in writing, Neal Adams has added the drama, shock-value, and awesome visual appearance which has brought the plots to life. By this point, Adams had already made a name for himself as star of visual storytelling at DC with his Batman tales in Detective Comics and The Brave and the Bold, but also in Strange Adventures starring Deadman. In an era today where the work of Neal Adams has been emulated – or attempted – by virtually every single artist working in comic books today, perhaps his lacks some of the magic which it undoubtedly enjoyed back in the 1970s. But even today, Adams captures something in his storyteller which no other artist does. Combined with O’Neil’s style and sense of storytelling, Adams makes each page panel look exciting, as if the motion of the characters and movement within a scene is visible in front of our eyes. Some of those famous moments – whether it be the scene from the first issue with Green Lantern speaking to the black tenant on the street, or Green Lantern revealing his disillusionment with the Guardians later in the run – could have been ruined or heavily dulled by an artist whose storytelling is static, and whose finishes are flat. Panels are drawn from an unusual and highly dramatic perspective, and while many of the inkers aid in creating that essential three-dimensional feel to Adams’s pencils. Dick Giordano easily provides the best service, with his flowing brush not just bringing Adams’s work to life, but also refining a few of the areas where Adams’s own heavy-handed inks could potentially badly affect a panel or page. Frank Giacoia’s inking, while perfectly adequate, seem to miss out some of the smaller details of Adams’s pencils, as if the brush contains too much ink. Dan Adkins translates graphite to ink more subtlety, but I think Giordano and later Bernie Wrightson are best. Overall, it’s difficult to put into words the true genius of Neal Adams and how much it adds to Dennis O’Neil’s writing. The way to get the clearest answer is to simply read the stories and absorb Adams at his best…

VERDICT

Overall, these first few issues of Green Lantern/Green Arrow mark an overwhelming change of direction not just for this title, but for the future of comic books. O’Neil’s writing focuses on the moral, social, and political questions of the early-1970s. It never speaks about such serious topics with the attitude a parent might have speaking to a child, where one is spoken down upon. O’Neil writes with a style which readers, regardless of age, can digest and enjoy. There may of one or perhaps two stories at most which fall short of the insanely high quality of writing seen throughout, but if you think that the peak of the title has passed, just you wait!

Next Week: Green Lantern/Green Arrow: Snowbirds Don’t Fly (Green Lantern (vol 2) 83-87, 89, The Flash (vol 1) 217-219, 226). Written by Dennis O’Neil with art by Neal Adams,

Comments