POST 228 --- BATMAN: GOING SANE

- Scott Cresswell

- Jul 16, 2023

- 11 min read

When it launched in 1989, Legends of the Dark Knight was a very different title compared to either Detective Comics or Batman. For starters, Legends of the Dark Knight was set outside the contemporary timeline. Many of the stories took place around the same time as Year One. It was also, therefore, a project which focused on a very different kind of Batman. This is a Batman who is still trying to find his wings. Less smart, less able, but perhaps more emotionally fuelled, this Dark Knight appeared in stories which were less conventional and occasionally enjoyed a psychological slant. The title began with four five-parters, all of which I’ve reviewed around this time of year. Shaman, Gothic, Prey, and Venom, whatever flaws they may have, are classic Batman tales, and it was a slight struggle to find a multiple-part Legends of the Dark Knight story to focus on for the blog’s fifth year. And that’s when I thought about this one. The best Legends of the Dark Knight stories are the ones with an original and unique idea. Going Sane has that - what if the Joker became sane?

Going Sane is a four-part story printed in The Legends of the Dark Knight 65-68 from November 1994 to February 1995. Written by J.M. DeMatteis of JLI fame, it was drawn by Joe Staton and Steve Mitchell. Although somewhat forgotten, Going Sane has been reprinted in a trade paperback, which also included Legends of the Dark Knight 200, a one-off featuring the Joker.

Out of all the comic book villains who have ever been created, few can doubt that the Joker is the most famous and highly acclaimed. Created in 1940 by Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Jerry Robinson, the Clown Prince of Crime became the Dark Knight’s most destructive and unbeatable foe. The completely unpredictable and insane personality of the Joker clashes loudly with the dark detective’s belief in logic. Other Batman foes have gimmicks or leave clues to their crimes – the Joker rarely does such a thing, and he’s one of the few who can really get to Batman’s emotions and incur his wrath. Forever, the Dark Knight has to resist that temptation to murder the Joker. Throughout the years, many writers have explored the Joker, his personality, and his clashes with the Dark Knight. Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s The Killing Joke springs to mind, and is considered one of the three ultimate Batman classics (along with Year One and the Dark Knight Returns, both by Frank Miller). Others have been well-received, like The Man Who Laughs, Mad Love, and many stories in the mainstream titles like A Death in the Family, or The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge. Going Sane is sadly forgotten, but with a fantastic concept and much else to say, I think it deserves to be looked at and remembered.

J.M. DeMatteis kicks off Going Sane with the Joker at his most wild. At a carnival, dressed as a clown and juggling to the amusement of the crowd, the Joker is playing to his audience who lap up every second of his act. At first, DeMatteis paints a picture of a classic silver age Joker, one who cares little for killing, and more for silly gags such as pies in the face. It’s in that moment when the Joker drops his juggling balls and they explode, killing four and injuring seventeen innocent civilians. With that, the Joker’s complete unpredictable nature is set. Throughout the first part, DeMatteis presents us with the similarities between the Dark Knight and the Clown Prince of Crime. Their shared determination, their outsider status within society, and of course their common attribute of survival against the odds. It’s pretty obvious stuff really, and focusing on the relationship between The Joker and Batman has been done better by writers like Alan Moore and Frank Miller. Nonetheless, it does create the scene and presents us with a Batman of raw emotion, one who hates the Joker to the near-point of recklessness. And this is where the story really begins. For some slightly unclear reason, the Joker kidnaps Councilwoman Elizabeth Kenner. He then takes her to an abandoned theatre and beats her senseless when she fails to laugh in front of repeats of Charlie Chaplin. Batman turns up to defeat the Joker and rescue Kenner. This is where the early Dark Knight’s mistakes come in – Batman fights the Joker, but it’s revealed to be one of his goons in disguise. Then Batman does rescue Kenner, but becomes trapped in a house full of explosives. The Dark Knight, while not caught in the direct blast, is badly injured and the Joker finds his unconsciousness body. He can’t believe it – is Batman dead? While the whole point of the story would be vaporised if Batman didn’t appear dead here, it is puzzling why the Joker doesn’t shoot Batman for good measure? He doesn’t really check at all – he just notices the unconsciousness body and takes it as gospel that he’s dead. Either way, the Dark Knight’s body is thrown into the river and, instantly, a change occurs within the Joker.

The Clown Prince of Crime’s comedown from insanity is conveyed very well, if somewhat on-the-nose at times. The Joker realises that with Batman dead (he thinks), his purpose is now over and there is no reason to be the Joker any longer. This is a staple of the Joker’s personality which all writers since the 1980s have accepted – the Joker exists only for Batman. As the Joker said in an episode of the animated series, “without Batman, crime has no punchline.” Where much contention arrives is what the Joker would do next. To writers like Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, the Joker has an aversion to killing Batman much of the time anyway, because he fears of what his life will be like without the Dark Knight. In my own humble view, and I accept its grimness, I would reckon the Joker would vanish all-together after killing Batman, possibly even through suicide. It’s because of the total obsession with Batman that you can’t imagine the Joker’s life without him. But to DeMatteis, the Joker can now move on and get on his with life. This change in the Joker’s personality is also displayed flawlessly well by – perhaps surprisingly – the lettering. As letterer, Willie Schubert does more than simply repeat the words written for him in a script. Throughout the first part, the Joker’s internal dialogue and captions have been written in somewhat scratchy and insane-looking text. With the Joker’s role now fading and normality returning, visually the dialogue appears less jagged and is calmer. It no longer looks insane, and I think as visual storytelling goes that is a true highlight.

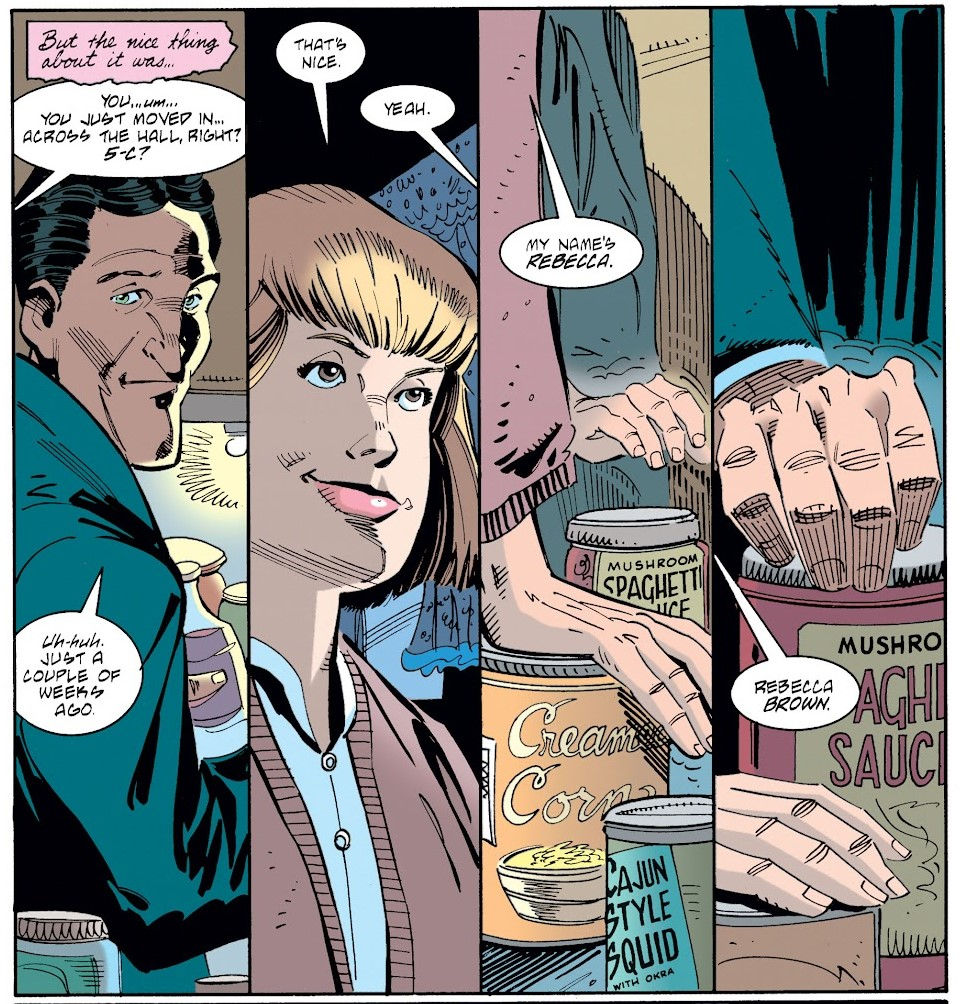

With part one’s fantastic ending, the second part shows a very different Gotham City. Batman and the Joker are both missing, and Commissioner Gordon is under pressure by Councilwoman Kenner for his failure to arrest the Joker (Gordon does embarrassingly very little in this story). While no one has seen hide-nor-hair of Batman, the Joker has got a completely new identity. Thanks to plastic surgery, Joseph Kerr now appears to be a normal-looking man, living in a nice little apartment after inheriting money from his long-dead parents. He even runs into a neighbour, Rebecca, who becomes his girlfriend.

Life seems almost too dreamy for the Joker and a bit too unrealistic, especially when it comes to the money and the house. It’s happens too quick, but what’s for certain is that new life isn’t that comfortable. DeMatteis paints Joseph Kerr to be a considerate, sweet, and kind man. But that darkness remains. Although Joseph Kerr now appears sane, I do love how DeMatteis continues to explore the Joker’s madness. He is haunted with dreams of his past, and on occasions dark memories from his time as the Joker seep through the façade of sanity. DeMatteis conveys this with brilliant visuals, ranging from Joseph Kerr staring deep into space reflecting on his bad deeds, to his nightmares featuring a cluster of insane words and dialogue balloons from the chaotic ‘Joker’ side of his personality. It’s all very creative, and the battle within the Joker means that you know – by the end of the story – that the Joker will return in full force. But there will be emotional consequences to that. Rebecca is written to be not just sweet and kind too, but also understanding. She isn’t frightened of Joseph Kerr’s dark side, and since DeMatteis creates a strong relationship between the two characters that we, as readers, can sympathise with, you care about the relationship and how it could end disastrously. Overall then, DeMatteis does create a nice world for Joker in Joseph Kerr, but it does focus strongly on the darkness within, and that’s because it’s bound to explode once again and take over. The second part does also focus on another character under emotional strain – Alfred. DeMatteis uses no words in these scenes to display Alfred’s depression that Bruce may be dead. As a character who rarely shows much outward emotion, this method of quiet and implicit storytelling speaks volumes about the strong bond between the Butler and the Dark Knight. Batman is ’dead’ for six months, but at the end of part two, he returns. There’s unfinished business.

Part three is probably the least interesting episode of the four parts. It looks primarily at Batman and where he was for the past six months. An explanation for this was always essential obviously but compared to the drama of Joseph Kerr and the Joker, Batman’s side of the story is duller. Found on a riverbank miles away from Gotham, Batman is taken in by Lynn Eagles, a doctor who restores him to full health over the course of several months. The big secret is that Doctor Eagles pretends not to recognise the Dark Knight from the start. Already, there is a feeling of strong loyalty, and DeMatteis back it up with a sad backstory. When living in Gotham, Doctor Eagles was raped. Several months later, she was attacked on the street, but on that occasion, she was rescued by Batman. DeMatteis does go out of his way to create an interesting personality for Doctor Eagles, but Batman’s recovery and these scenes feel like a brake on the main story. It’s simply a long-winded excuse for Batman to be written out of the story while the Joker can enjoy the ups and downs of his new life. The Dark Knight doesn’t shine much at all in Going Sane, but that’s because he’s not meant to. Going Sane is a Joker story. The Dark Knight’s return to Gotham focuses on his quest to find the Joker. We’re given some action when Batman tracks down the wife of the criminal plastic surgeon who restored the Joker back to health from his skin condition and green hair before he was murdered, and in the end the Dark Knight finds the Joker’s home address through one easy clue – Joseph Kerr. That name is the biggest clue the Joker could leave. I did say earlier that the Joker rarely used clues, but this clue is different. This is Joker appearing through Joseph Kerr subconsciously – he is trying to break through sanity and take control once again. The Joker’s new name is not just a reminder of the past, but also a sign of who Joseph Kerr once was. It’s the perfect bait for Batman, and Joseph Kerr doesn’t even realise that the Joker has done it. It’s a fantastic piece of writing by DeMatteis, and it leads fantastically into the last part.

Going Sane’s ending is the same as how the story started – with the Joker threatening to kill Councilwoman Kenner once again. But what led to this has to be one of the best moments in the whole story. By this point, Joseph Kerr has proposed to Rebecca, and she has accepted to marry him. But one day, while out on a walk, Joseph Kerr’s life comes to an end. He finds a newspaper, with the main headline conveying Batman’s return to Gotham.

Instead of a sloppy and on-the-nose transformation from sanity to madness in a matter of panels or pages, DeMatteis handles this charged moment flawlessly. With the Joker’s return, he doesn’t get the knife out and kill Rebecca, nor anything of the kind. He simply tells her that he left something behind at home, and he’ll come back for her soon. This is the last time Rebecca saw Joseph Kerr. The fact that he doesn’t kill her or ever meet Rebecca again is a blessing. It would be too dull, expected, and frankly tiresome if the Joker did try to kill her. If anything, Rebecca being left in the lurch forever is a more devasting ending because she really loved him and, for just a few moments in the story, readers believed that there was some hope for the Joker and that he could lead a normal life. That hope is deflated, but Rebecca’s survival and the Joker deciding not to go for her means that all hope isn’t lost. With that, the Joker returns to the fray. I’m not quite sure how he transformed his skin, lips, and hair back to white, red, and green permanently. I doubt he threw himself back into that vat of acid, but it isn’t really that big a deal when you think about it. The return of the insane Joker means that Going Sane is over. Batman defeats the Joker and puts him behind bars, and Councilwoman Kenner is rescued one last time.

If you were to ignore the ‘Going Sane’ part of the story – from Batman’s death and the Joker’s turn to sanity, to Batman’s return and the Joker’s return to madness – then this story would be pretty forgettable. The Councilwoman Kenner plot isn’t particularly appealing or interesting, but it's made better by the drama of the Joker. And that’s why Going Sane is something of a Joker classic. It’s an original idea that hasn’t been played with much before, and the world that DeMatteis creates for Joseph Kerr and its details is wonderfully done. It involves the readers with the drama too, and by the end you leave with a different impression of the Joker from when you started. It’s a different type of exploration of his character. We’ve seen plenty of writers look at his insanity and obsession with Batman, but few have looked at other parts of his personality, and that’s what Going Sane does very well. Other than that, we’re presented with a more amateur Batman, and there are some good moments with him, but as I said, he doesn’t dominate the story much and that’s how it should be. All-in-all, this story belongs to the Joker more than anyone else.

At first glance, Joe Staton would appear to be a wholly strange and undesirable choice as artist. That’s not just because of his usually cartoony style, but also because his pencils suit a different era of comic books. He’s work for the relaunched All-Star Comics in the 1970s beautifully recreated the 1940s era of the Justice Society. But for Going Sane, Staton clearly has adapted to this darker mood. It never looks too bright or garish at all, but more to the point, the style of art manages to look both cartoony and serious at the same time. The Joker is drawn to be an exaggerated figure who appears very comically, but the muted colouring and slightly scratchy inks by Steve Mitchell give the story a much darker look. Overall, there is a lot of Staton still present in its style, but it has been updated, even if the final inks by Mitchell can vary in quality.

VERDICT

Overall, Batman: Going Sane is a classic Joker story more than anything else. J.M. DeMatteis explores the Joker’s personality unique and from a different angle as opposed to previous stories. The world of Joseph Kerr is fantastically complex, and many of the plot choices to do with the Joker and his brief leave of absence from madness is flawless. Compared to that, the rest of the story does pale in comparison, but nothing stoops down to a level of utter dreadfulness. Batman may be present, but he doesn’t shine, nor does any other main character. Going Sane is a memorable Joker story, and it shouldn’t be forgotten and left behind in the shadows by the likes of The Killing Joke.

Next Week: Justice League: Injustice League (Justice League (vol 2) 30-34). Written by Geoff Johns, with art by Ivan Reis, Doug Mahnke, Scott Hanna, Keith Champagne, Christian Alamy, and Scott Kollins.

Comments