POST 202 --- LEGEND OF THE DARK-MITE

- Scott Cresswell

- Jan 15, 2023

- 10 min read

Let’s face it – comics have always been a bit weird. I don’t mean any obsessions about the genre, but more the fact that most comics feature a grown-up guy in a tight costume with a range of superpowers. But remember when comics were even weirder? To me, there have been at least two decades where mainstream DC Comics were at their most ludicrous and odd. While far from universally accepted or even binding, the two decades (to me at least) are the 1950s and the 1990s. The first full decade of peace after war, comics of the fifties represented an era of fantasy. Gone were the dark days of ‘our heroes’ fighting in the fields – kids wanted to delve deep into science fiction and fantasy tales. As for the final decade of the twentieth century, while grimmer and more violent than the content of the fifties, sixties, seventies and even much of the eighties, writers like Grant Morrison (especially with his The Invisibles saga) side-stepped back into the absurdity – just with more guts and gore. This theme is really the only element that links the colourful comics of the 1950s and grey graphics of the 1990s. And perhaps this explains the thinking behind why Alan Grant, a veteran in the English and grimy way of comics, could revive a 1950s impish character for children forty years later to some success…

Alan Grant, who died only last year, will be remembered – above all else – for writing Batman. During the 1980s and 1990s, his name has found itself on countless comics and is remembered for creating some of the darker villains of the time. Yet, one of the most underrated and forgotten stories of his has to be from Legends of the Dark Knight 38, published in October 1992. Entitled Legend of the Dark Mite, the story was followed up by a prestige format book called Mitefall (released in March 1995). Both drawn by Kevin O’Neill (also recently departed), who was the lucky star of their own prestige format book launched by just one issue in an ongoing series?

Enter Bat-Mite. Created at the tale-end of the decade in May 1959, Bat-Mite was created by Bill Finger and Sheldon Moldoff for Detective Comics 267. Supposedly a magical imp from the mysterious Fifth Dimension, Bat-Mite was an avid watcher of Batman and Robin in their war on crime in the silver age. A diehard fan, Bat-Mite decided to present himself to Batman by dressing himself as the Caped Crusader and following him around. In short, he was a pest with magical powers. Looking back, his first debut in that issue of Detective Comics was a clear sign that Batman was losing what made it unique and ended up delving far too much into the fantasy zone. That said, Bat-Mite has always been more memorable than most of those other aliens that Batman bumped into during that era. Bat-Mite, while irritating, had humour and mystery to him. Often, he teamed up with Superman’s foe Mister Mxyzptlk, a chum from his dimension, and together they caused trouble for the World’s Finest duo. But with the silver age’s death in the 1960s, there was no room left for cosmic shenanigans of this kind. Bat-Mite was locked away in his box before, three decades on, Alan Grant let him out of his box.

Legends of the Dark Mite

The Legends of the Dark Knight title was unarguably a great launching pad for some fantastic stories featuring the Dark Knight. It allowed for longform stories and multi-part tales to flourish more than in Detective Comics or the main Batman title. While the first twenty issues of the title were filled only by four five-parters, later issues were self-contained. Legends of the Dark Knight 38 had the treat of reviving the inter-dimensional imp. However, Grant adapted the character flawlessly with the times. Legends of the Dark Mite – a fantastic title – begins typically as a 1990s story. In a darkened interrogation room, Batman confronts a crook named Bob Overdog. Unlike some of the Dark Knights more prestigious foes, Overdog is small fry with a small brain spends his days on amphetamines and hanging out with gangsters who can get him more drugs. In short, he’s a druggie. And like other druggies, his vision plays tricks. While on the hunt for more drugs – despite already pumped to the brim with enough of them – with his gang, he is caught by Batman, and he attempts to escape into a dark alley. It is there, standing on a dustbin with a disapproving look, where Bat-Mite stands. Looking exactly the same as the imp did in the 1950s, Bat-Mite disarms Overdog with magic before the rest of his gang arrive. As the criminals fire hot lead into Bat-Mite, the bullets go through him, and the sweet creature transforms into a vampiric-like monster. He kills Overdog’s gang, leaving just the man himself. From there, he abducts Overdog and throws him full force into the Fifth Dimension. Words cannot explain fully what Overdog sees in there. Perhaps some visuals would help

In this dimension also lurks other similar creatures to Bat-Mite, all of whom are based on Batman villains and allies alike, along with other stars of the DC Universe like Superman, the Flash, Lobo and many others. The experience becomes too much for Overdog, who caves into all sorts of mental pressures before coming to two conclusions – either this is all in his mind, or Bat-Mite is God. His cosmic adventure ends when Batman finds him alone crying in a dark alley. From there, it’s straight to Arkham for Overdog, who keeps begging his doctors that the drugs are behind his visions of Bat-Mite. “I’m not mad!” he screams as Bat-Mite appears from thin air in his cell before vanishing as the doctors arrive to sedate Overdog. Flawlessly, Grant disguises the origin of Bat-Mite. Is this being the same Bat-Mite from the silver age, or is he part of Overdog’s drugged-up imagination. This mystery – and the real sense of surprise and absurdity – fuels this story and makes it a memorable classic. Overdog is a good unreliable narrator, Batman works at his best here as a witness to events beyond his control, and Grant concludes the story with fantastic mystery as the Dark Knight flies away only for Bat-Mite to appear into reality once again, unknown to Batman. Bringing back Bat-Mite in a very different era of comics could have been embarrassing – worse still naff. Instead, Grant balances out this crazed concept with some much-needed modernisation with doesn’t stray too far from the original creation. As a story, it’s a pleasant one-off. Will the magic keep for a full-sized special?

Mitefall

After Legends of the Dark Knight 38, an editor or perhaps even Grant himself is obviously thought that the revived Bat-Mite had potential for more stories. I don’t know how Dennis O’Neil – the editor of the Batman titles from 1986 until 2000 – would have

reacted if someone had told him in the seventies that he would be partly responsible for giving Bat-Mite his own fifty-page story. Regardless, Mitefall is based heavily on a project from the nineties. The Knightfall saga (consisting not just of the 19 issues of Knightfall, but also 26 issues of Knightquest: The Crusade, 9 issues of Knightquest: The Search, and 10 issues of KnightsEnd, along with 3 aftermath issues at the end) was the overarching story for all Batman titles from April 1993 to September 1994. Broadly split into three acts, the first featured Batman squaring up against the new villain Bane, who breaks the Dark Knight’s back, and the heroic mantle is passed temporarily to Azrael who – as a rougher and tougher Batman – defeats Bane. Act two focuses on Azrael and his move towards directionless violence as he ruins Batman’s reputation for justice. Lastly, act three is the comeback for Bruce Wayne, who returns as Batman to take back his place by defeating Azrael. With a real mixture of talent present both in storytelling and artwork, Knightfall is a grand – if overlong – classic. So, how can Grant condense nearly 70 issues down into fifty pages and provide a cosmic fifth dimensional spin?

Grant begins Mitefall just after the events of Legends of the Dark-Mite. In Arkham, Overdog is counting the days down, still no sign of Bat-Mite. But suddenly, six days into his confinement, Bane launches an attack on Arkham to break free all the insane villains. This is exactly what happens in Batman 491, the prelude issue to Knightfall which kicks everything off. Overdog is a witness to the events of this issue. So, technically, Mitefall is linked to Knightfall fairly directly. However, Overdog may be let out as well, but the Joker wastes little time on him and shoots him. You see, Overdog has seemingly (in the space of six days) transitioned from crime to enlightened justice. His failed attempt to fight the Joker lands him with a bullet in his body. At least, so the Joker thought. It turns out that the bullet hit Overdog’s diary – meaning the questionably reformed druggie to head out onto the streets. Confronting other escapees on the way, attempting to convert them to good, Overdog doesn’t do himself any favours. He ends up getting beaten up before Batman arrives to defeat the escaped crooks. In that time, Overdog escapes to the roof of an abandoned church and sleeps. This is when the weirdness starts.

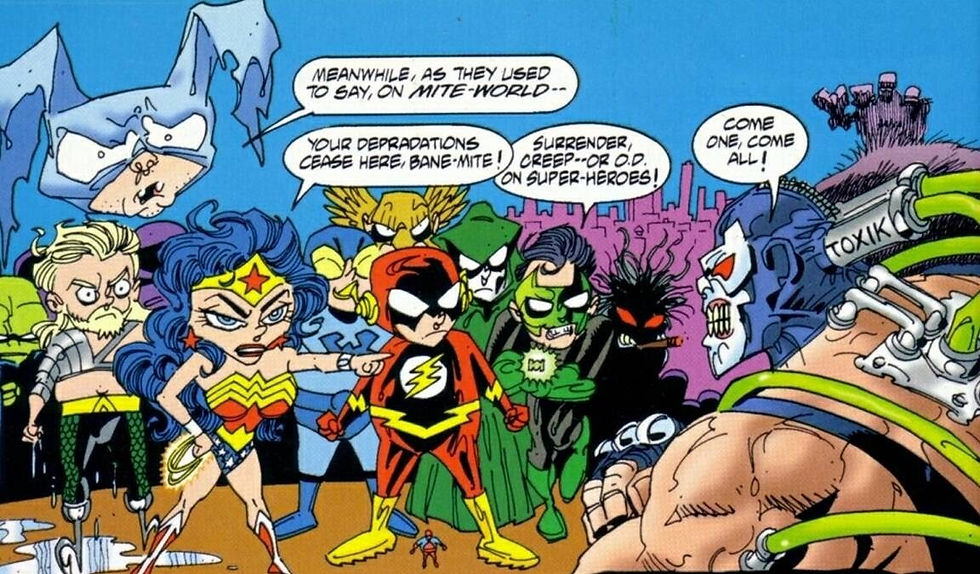

Bat-Mite materialises in the real world, attempting to get the help of Batman. Instead, he seeks Overdog’s aid. It turns out that the same event which has happened in the Dark Knight’s world has occurred in Bat-Mite’s dimension. In the Fifth Dimension, Bane-Mite released all the inmates from Arkmite Asylum before the drugged-up villain broke Bat-Mite’s back. With Bane-Mite now ruling the Gotham of Bat-Mite’s world, he enlists the help of Overdog (of all the people!) to bring down the villain. At first, Overdog is apprehensive and is confused about whether Bat-Mite exists or not. However, he is convinced by Bat-Mite and – in effect – he becomes the Azrael of Bat-Mite’s world. The story copies pretty much the same line of route as Knightfall, except there is a little bonus as all the other heroes from Bat-Mite’s world attempts to defeat Bane-Mite on their own.

In short, it doesn’t go well. Even Super-Mite fails! With the powers of Azrael, Overdog charges into the Fifth Dimension, refusing the help of the dimensions more mystic heroes (like Swamp-Mite and Sand-Mite (Dream)). Even with a Bane-Mite on hard toxin drugs, Overdog is successful, and the ultimate foe is defeated! But suddenly, it all goes wrong for Overdog. Failing to ignore his addiction to all kinds of substances, he takes one smell of Bane-Mite’s toxin, causing his head and skull to immediately explode. Meanwhile, back in reality, Overdog is found dead – he fell from the church roof to his death. Grant’s creative instinct for good character writing shines here as we see two very different tributes to Overdog. In Batman’s world, Overdog’s life is summed up by the words of a police officer – “He was just some worthless junkie!”. These harsh words are missed out in the Fifth Dimension. There, Bat-Mite unveils an immortal statue to Overdog, and he becomes a legendary hero for his actions there. This ending – tinged with both sadness and jubilation – gives Mitefall a memorable end. As for the rest of the plot, there is little really original here. The first scenes are based heavily off the beginning to Knightfall, while the rest of the story has been adapted from Knightfall only. Overdog doesn’t live long enough to see his descent into darkness, even though we got a strong taster of it as his fatal addiction to drugs gets the better of him. Grant makes Mitefall unique not just because of its humour and character, but because of the inclusion of other DC stars in the Fifth Dimension. Grant is only one of two writers to give the Fifth Dimension a plethora of characters to play around. The other writer is Evan Dorkin, who scripted the excellent World’s Funnest (2000). They both added character to the Fifth Dimension and expanded it to make it into another kind of Elseworld.

Since Mitefall is far more action-based than Legends of the Dark-Mite, there really isn’t much room present for a relationship between Bat-Mite and Overdog to breathe. Sure, Overdog’s view of Bat-Mite changes and – in the end – the imp sees the druggie as the hero, but there isn’t much friendship or background present. It’s right that Bat-Mite remains something of a mystery, but Overdog? There isn’t much on his background or character. Often, he can be a bit flat and it’s difficult to warm to him. He felt slightly more interesting in the Legends of the Dark Knight tale rather than this longform work.

Regardless, it’s hard to really criticise Mitefall. Much of the content has been lifted by Grant from another of his stories, and I think on the whole he adapts it well. I like the introductory pages where Overdog’s world feels incorporated into Batman’s own. Overdog may be an entirely forgotten character as he leaves little – if any – legacy in Batman’s world, but I think it’s sweet that to Bat-Mite’s world he is a titanic hero.

Kevin O’Neill is not an artist who one would usually see in a DC Comic. Famous for The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (penned by Alan Moore), O’Neill’s style of art wouldn’t appear to mesh particularly well with the colourful insanity of the Fifth Dimension. Yet, O’Neill captures that scatted-brain idea successfully. In Legends of the Dark-Mite, O’Neill’s art is suited to the gothic backstreets of Gotham, and while his illustration of Bat-Mite is sweetly reminiscent of Moldoff and Sprang, his 1990s vampiric version of a dangerous Bat-Mite is fantastic. As for Mitefall, O’Neill captures the silliness well. Although sometimes too cartoony for its own good, the Fifth Dimension’s appearance is certainly memorable and O’Neill’s energic way of telling stories is highly memorable. Overall, a style that wouldn’t usually work with such pesky imps is pulled off well.

VERDICT

Overall, Legends of the Dark-Mite and Mitefall are two forgotten stories that should be remembered more. While lacking in storytelling substance and far from original, it presents Grant’s talent for bringing back old concepts and reviving them respectfully. O’Neill’s art adds greatly to Grant’s writing too. The fact that Mitefall and the revived Bat-Mite from this era is now buried under decades of more content shouldn’t dampen the quality of Grant’s writing and O’Neill’s art. While never ground-breaking, these two stories are entertaining and – to me anyway – memorable.

Next Week: Green Arrow: Year One (1-6). Written by Andy Diggle with art by Mark (Jock) Simpson.

Comments