POST 184 --- LONDON'S DARK

- Scott Cresswell

- Jul 24, 2022

- 7 min read

Isn’t this something of a surprise. Since I am unable to deliver another review from the titanic Keith Giffen and J.M. DeMatteis Justice League International series, I thought I’d explore something a little different. In any creative field, all writers must start somewhere. Whether it be in a small-print cult magazine, or even in the back of a newspaper, a creator must create roots before they can be great. For James Robinson, the excellent writer who wrote Starman for DC from 1994 to 2001, along with some other incredible stories such as JSA: The Golden Age and Batman: Face the Face, his start came with a very different kind of tale. While Robinson may be in love with the world of old, London’s Dark, “a tale of love & war, life, death (& aftermath)” (as described on the book’s cover) explores war-time Britain and the Blitz, but with a twist. When I first read this, I thought that Robinson was writing some kind of historical fiction with no ounce of super heroism in sight; I was wrong.

London’s Dark was published as a square-bound deluxe edition graphic novel, published by Escape/Titan Books in 1989. While written by James Robinson, it was

pencilled and inked by Paul Johnson with his noir style. I’ve read London’s Dark in its original graphic novel.

If this was Robinson’s attempt to write a rather soppy story featuring gangsters set at the height of the Blitz in 1940, then there really wouldn’t be anything to hook a superhero fan like myself. But despite an apparent absence of anything like that in the first few pages of London’s Dark, it undeniably has a great hook to begin. In the dim and dark wet streets of London during an air raid, a man named Harold Stevens is killed by the mob. It’s not only a very aggressive start, but it raises so many intriguing questions for Robinson to answer. In short, it begins as a murder mystery. Next thing you know, Robinson throws us four months into the future and that is when we are introduced to the main character. Jack Brookes, an air raid warden, is pretty much your average guy from the 1940s, and were it not for the strange events that he latter becomes involved with, he would be remembered for having a character as interesting as cardboard. Either way, the character who gets Jack involved in the main plot is Mrs Stevens, an old woman whose son Harold (as we saw in the introduction) died. She heads to a Sophie Heath, a psychic with the power to communicate with the dead. She is the one to tell Mrs Stevens that her son wasn’t killed by the bombs, but rather he was murdered. You’d think, at first anyway, that Sophie was a con-merchant who effectively gained money for false services. However, since Robinson has already shown from the very start that Harold was indeed killed, the revelation that Sophie does possess some kind of supernatural power isn’t surprising. This proves that the two-page introduction featuring Harold’s death, despite its great hook, destroys any mystery surrounding Sophie. This moment basically just tells she has superpowers, and when Jack visits her in order to help comfort Mrs Stevens, it really isn’t much of shock to find out something deeper is going on. Anyway, for reasons which are very cliched, Robinson feels the need to throw in a love story here between Jack and Sophie. It’s extremely predictable and there isn’t much reasoning behind their love, but I suppose it sets up some emotional chemistry for later events. One of those latter events occurs throughout this story, and it is mob planning their next moves. After hearing about police investigations into Harold Stevens, they decide to go after Jack (continued)

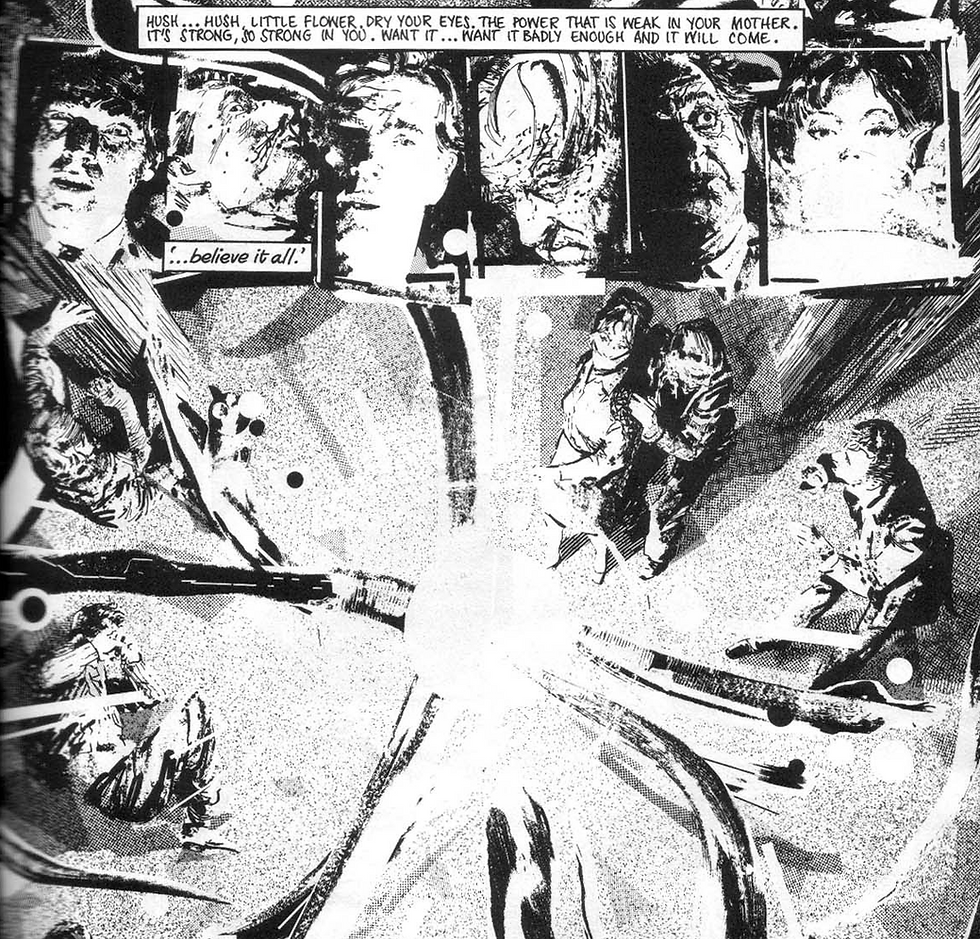

and Sophie. But before all this happens, Robinson unleashes his verbosity (if it wasn’t already present enough) as two pages are prose-based. The inclusion of a prose insert isn’t unwelcome, nor a problem. The only issue is that a simple story is told for too long, and it ends up being slightly dull. It’s basically about how Sophie’s mystical powers are hereditary through her grandparents, and she just tells some anecdotes about them and their powers. The quality of Robinson’s prose isn’t terrible or bad, nor perfect. But it’s a nice touch. Speaking of prose and dialogue, one of the most annoying aspects of London’s Dark has to be its lettering. While it is adequate in most instances, occasionally Robinson will change the entire font for a page or panel, and sometimes it can be literally unreadable. I’ve never been a huge admirer of that handwritten script font, but here it is truly atrocious. Apologies for getting a tad off topic, but it really bothers me. As for the main plot after the story of Sophie is told, there really isn’t much else to say. The love story between Jack and Sophie develops, if that is the word to use, and everything leads up to an explosive finale featuring the mob. As I said, the path towards that finale is pretty rudimentary and it features little content of significance. On the other hand, the finale scene is the place where the questions about Harold and the mob are to be answered. It turns out that Harold was forced to work for the mob and deliver them goods, but one day he wants out and the mob, predictably, would rather kill him than give him freedom. Again, it’s a fairly standard moment and there isn’t much surprise to the revelation. From there, the mob try their best to kill Jack, but Sophie intervenes using her psychic powers. Unfortunately, the artist lost all skill here and the moment becomes an unintelligible mess. Some explosions happen, and then a bomb falls out of the sky, and when the artist’s ‘skill’ returns, Jack and Sophie are found injured, but alive. I guess it’s up to us to fill in the blanks. In a way, I’m kind of disappointed about the ending. Sure, it’s a happy one as the main characters live and the mob die, but since this is the only story, we’re ever going to read with these characters in, I thought a major death wouldn’t have been bad. After all, it is a war featuring some gangsters and psychic powers. The stakes were high, and some results of the danger would have been great. Crap, I’ve realised that I’ve spent the whole time just dissing London’s Dark off. When you examine this story in detail, then its faults are highly visible and distracting. However, there is a reason why this story was a springboard of sorts for Robinson, and it did land him some great writing duties at DC. Firstly, Robinson captures the mood of the era extremely well. While the artist may deserve some credit for the bleakness of London’s Dark, Robinson’s sense of character writing and descriptions of the world in 1940 are fascinatingly real. He can capture the mood successfully. Secondly, Robinson’s sense of storytelling is very creative and often unique. Throughout, even in moments of dullness, the writer adds some creative flair to each page, whether it be through page layouts or how certain dialogue is written or shown. Robinson explores different ways of writing and despite a pretty standard story, he tells with a surprising amount of creativity. That said, one of the story’s most prominent problems is that it is overly verbose or too dialogue heavy when it doesn’t need to be. However, thirdly and finally, Robinson creates an interesting, if not wholly successful, structure for London’s Dark that makes it engaging. For example, despite its flaws later, the hook at the start was enough to drag me in, and the way certain story elements are structured or paused until a later scene for suspenseful reasons is great. The only problem with this structure is that there isn’t enough plot or action to really fill or complement it. London’s Dark, for all of its great atmosphere and creativity, has a shallow and somewhat cliched plot. The inclusion of supernatural elements may be good, and it does spice things up, but there is little else here to really transform London’s Dark into a classic.

You may have noticed some of the subtle hints I’ve left concerning my views on Paul Johnson’s artwork. Before I get into the thick mud of criticism, I have to admit that the visual tone of his art is brilliant. The lack of any colouring makes London’s Dark look, on occasions, like a noir classic. Perhaps it really would be one were it not for the sloppy and amateurish details drawn by Johnson. At times, it is near impossible to work out what is exactly going on in a scene. The finale pages are a prime example of that. As a reader, you’ve basically got to guess, and that’s just bad storytelling.

Not only that, but the finishes are often sloppy and just look plain awful. Sure, there are some nice layouts here, but when the artist struggles to even draw or tell a pretty basic story, that’s never a good sign of anything.

VERDICT

Overall, London’s Dark deserves to be remembered as James Robinson’s first published comic book. That’s about it. At its best, it can exemplify his great writing qualities and how unique and creative he can be, but at its worst, this story can be shallow and dull. And any chance of making this noir world effective in its visuals is utterly destroyed by Paul Johnson. In short, if you want an early James Robinson story that is a classic and defines his artistic storytelling, read The Golden Age.

Story: 5.5/10

Art: 2/10

Next Week: Justice League International: The Teasdale Imperative (Justice League America 31-36, Justice League Europe 7-10). Written by Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, and William Messner-Loebs with art by Adam Hughes, Joe Rubinstein, Bart Sears, Pablo Marcos, Art Nichols, Bob Smith, Jose Marzan. Jr, and Tom Artis.

Comments