POST 144 --- UNCLE SAM

- Scott Cresswell

- Oct 17, 2021

- 7 min read

What’s the first thing that comes into your head when you think of Uncle Sam? I don’t know about you, but my mind immediately transports me to Len Wein’s brilliant Justice League of America 107-108, where the star heroes end up, thanks to the Multiverse, on Earth-X, a planet where the Nazis were the victors in the Second World War. All hope, however, isn’t lost. A heroic team of patriots fight against Nazism and their leader is Uncle Sam, who represents humanity’s ultimate goal of freedom. That’s what comes into my head. Everybody else, I’d assume, would think of THE Uncle Sam, the personification of freedom and the spirit of the United States. Perhaps it’s because I’m not American, but the character from DC Comics is what came into my head the second I picked up Vertigo’s U.S. miniseries. Once again, I was wrong. Darnall’s Uncle Sam story isn’t your typical Vertigo tripe, nor any closer to the vibrancy of the

mainstream DC Universe. U.S. is a history, specifically one about the United States, and what aspects of its past it desperately wants us all to forget…

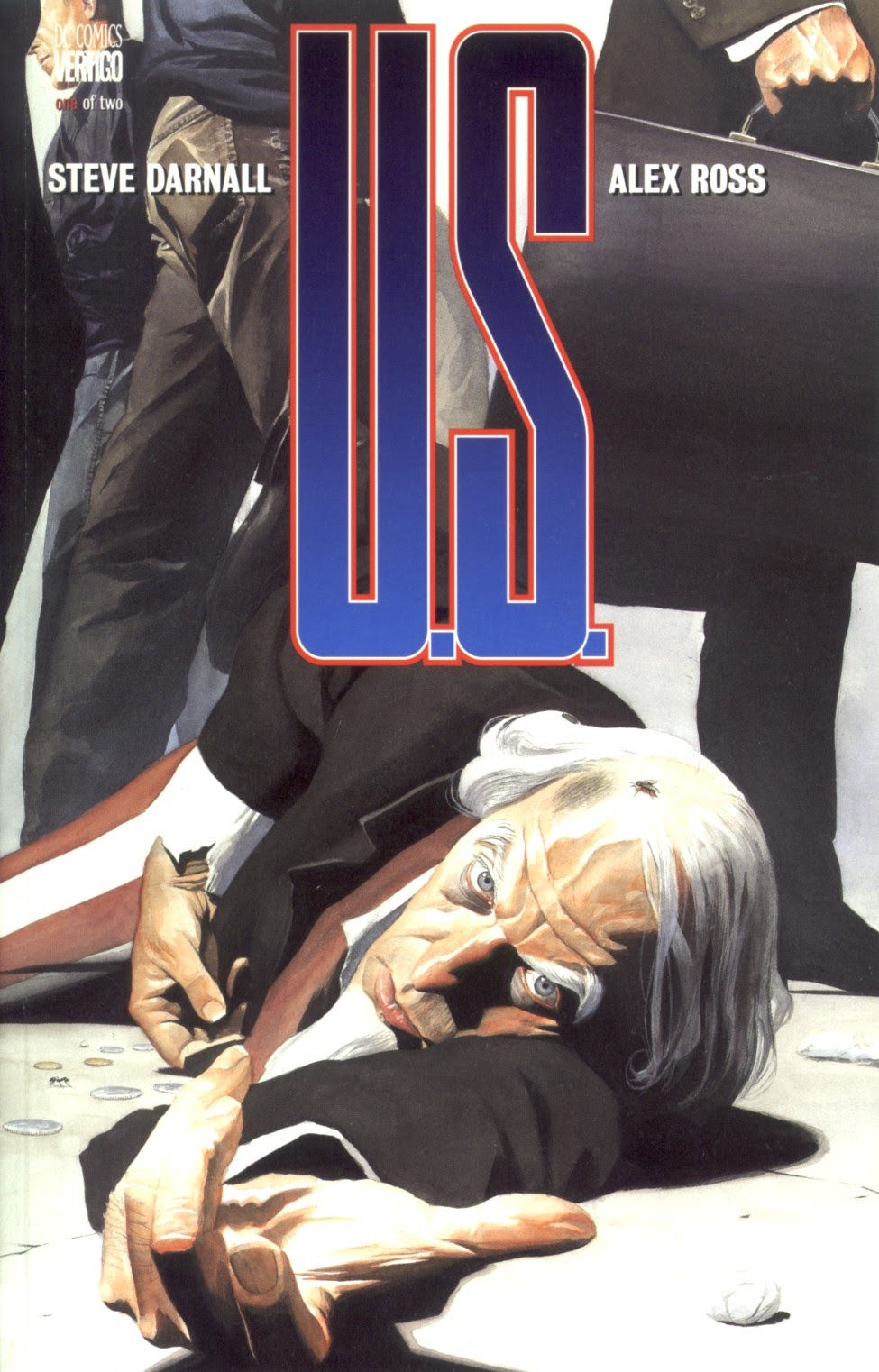

Uncle Sam, or U.S., was published from February to March 1997 as a two-issue miniseries. It was written by Steve Darnall with art by Alex Ross. I’ve read the story in its trade paperback.

The politics of the United States of America goes back a long way, but most of its historical cancers and troubles spawn with the American Civil War. While the Confederate States of America existed for only four years during the 1860s, the Southern states of today are almost like a different country from the rest of America. How could a person in Maine feel like they lived in the same country as a farmer in Alabama? It’s not just the distance, but their history. Attitudes to race, immigration, and politics are far different in the Southern states and history proves it. The point of Steve Darnall’s Uncle Sam isn’t just to explore America’s divided and fractious history, but then to justify that United States patriotism can’t be frowned upon if you exude the right morals. The Uncle Sam in this story is no hero, super or otherwise. He and his Freedom Fighters aren’t sung as heroes of democracy for they are as fictional as they are in our world. Instead, our nameless protagonist Uncle Sam storms into a hospital with nothing wrong him with, well, at least physically. Uncle Sam is mentally troubled as he spends most of his time quoting US Presidents from Washington to Reagan while walking alone through the streets of a 1990s American bustling metropolis. Throughout, Uncle Sam hallucinates moments from the past as he learns that his own vision of America, one that is focused on liberty, is false. Uncle Sam is suddenly transported back in time to the days of the American Revolution. His wife, Bea, strongly attempts to persuade him to stay out of the war, but the old patriot swears his allegiance to George Washington instead of the British King George III. Then, as just as suddenly as he entered the era of revolution, we’re back in the nineties and a homeless man steals Uncle Sam’s shoes. Even when I read this scene and expect it to come, its suddenness is still hugely powerful that’s the point. This is Uncle Sam’s character, forced to relive events in American history. Every time the nation cries, they come to me, he says. As an advertisement of patriotism, Uncle Sam was first used by the federal government in another US vs UK war from 1812 to 1815. Uncle Sam remains still the face of America and Darnall writes him as the country’s spirit personified. He feels every inch of American pain, whether it be the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963, the massacres of Native Americans during much of the 19th Century, the treatment of Union soldiers in prison camps, or the ongoing racial violence that has plagued the country for centuries. Darnall uses the first part of U.S. to not only show us how horrific American history is (like the histories of other dominant countries pre-1900), but to show that much of it is still continuing. When Uncle Sam isn’t tripping out and (continued)

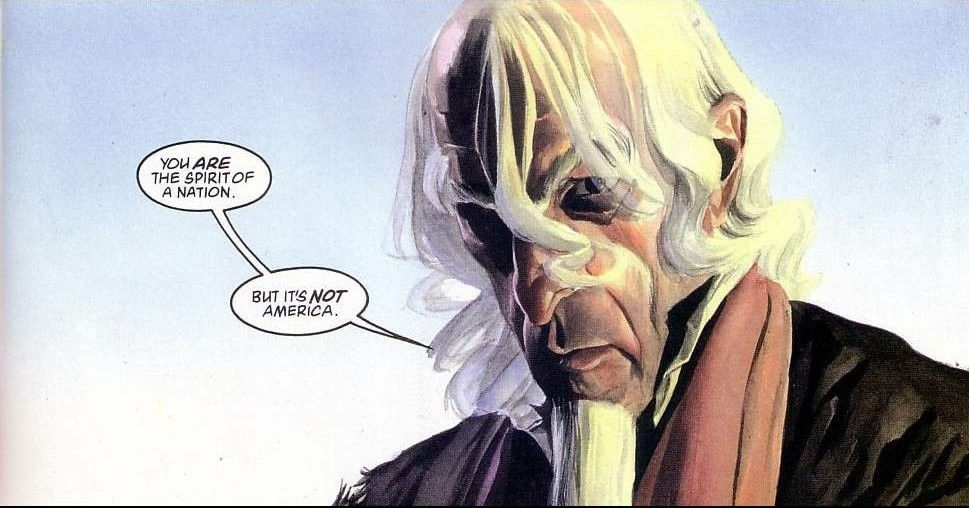

experiencing bloody events from the past, most of his wandering around during the modern day is taken up by an election campaign. That is when Uncle Sam isn’t exploring an old souvenir shop filled with American history (which causes most of the flashbacks) which may not even be real anyway. The campaign during the modern day is between “liberal” Democrat Rat Elliott, the challenger, and the Republican incumbent Senator Louis Cannon, who spent most of his campaign funds on attack ads, the famous, or perhaps infamous, being the use of the word liberal. Particularly after the Reagan revolution during the eighties, any politician calling themselves liberal were attacked and as such could effectively write off any chance of becoming President. Things have changed now, since the dreaded word socialism can now be uttered, but Darnall uses politics as part of the story to present how divided America is. Anyway, Uncle Sam attends Cannon’s victory rally after chasing a huge blow-up Uncle Sam balloon. As the spirit of America, Uncle Sam instantly sees through Cannon’s words of unity and love, before losing his temper with a hired Republican Uncle Sam impersonator. Uncle Sam ends up in prison with a group of young radicals severely opposed to Cannon. Although Uncle Sam screams and screams in his cell about how he is the only one who can save America, nobody listens. Darnall’s final page of the first part shows excellently that although Uncle Sam may want to be the savoir of America, he is coated in the blood of all its victims from centuries gone past. Part Two begins melancholically with Uncle Sam, again during the American Revolution, writing to Bea about fighting the British, before arriving back to modern day prison in his soiled red and white trousers. He manages to escape from prison, and he runs out into the crowded city streets just as the police were announcing that he was to leave in the custody of a woman named Bea. Before you can even try to think about how she can exist in the late 20th Century, Uncle Sam runs into a British armoured solider who is the personification of Britannia. She is a representation of Britain’s power in the world as a mighty female warrior with a fierce lion. Suddenly however, we’re back to reality as Uncle Sam is dunked in gasoline and set alight. But this is just another dream as Uncle Sam is impervious to flames as the living spirit of America. That doesn’t stop the emotional strain, however. Just like in the first part, Uncle Sam experiences all the injustices of America, its history, and what it is today, watching as he is forced to kill in war for his country. The rest of the story strays away from American history and goes more in the direction of mythology. Uncle Sam runs into that old souvenir shop again before ending up in a white heavenly realm where he meets Bea, or more accurately Columbia. As the female personification of America, she tells the story of America’s transformation after the First World War, and how the nation of idealism and unity turned into an ugly one of greed. The story culminates with Uncle Sam meeting Uncle Sam. As two giants of America, our Uncle Sam represents the America of freedom and idealism, while the other represents what the country has become. The figure of today uses violence as a means of defeating the past, but the morals of yesterday succeed. Uncle Sam of today may represent the Nation of today, but not true America. With a new dawn rising in America, the heroic Uncle Sam, with his old core values, puts on his famous hat and gleefully sings as he heads down the street of modern America. U.S. is written primarily as a history of the United States from the perspectives of figures of idealism. Where did America go wrong? Some would argue that while America got worse as the 20th Century progressed, that feeling of America First policy has always been present and always will be. Of course, America has the potential to do great things and it has and will do, but its dark history hasn’t gone away and quite frankly, they’ll always be a significant minority that won’t it to disappear. The US may be formed of 50 states under one union, but underneath it all, the union is fragile beyond belief. Moving on from the philosophy, Darnall writes a very entertaining and informative story about America and its past, present, and future. I’ve not discussed too much at great length here because I’d rather not. It may lose its way always towards the end with its dip into speculative mythology, but if you’re looking for a story with a strong protagonist that doesn’t pussyfoot around the idea of what American history really is like, then you’re in for a treat. And I haven’t even mentioned Alex Ross yet.

In comics, there are artists who draw great comic books. Jim Aparo is a prime example. Then you get some whose field is larger, like Neal Adams and Brian Bolland. But, standing tall at the very top of the art medium in general is Alex Ross. His paints and storytelling is obviously realistic, but Ross’s sense of storytelling works amazingly with a story with as much depth as this one. It’s great not because you look at it and think that it shouldn’t belong in a comic book. You look at it and think the opposite. Great artists like Alex Ross can transform how comics are viewed, particularly with a plot as adult and thought-provoking as Darnall’s. Words fail to describe in full Alex Ross’s genius. All you have to do is look at it and you are emersed in the world he has so carefully constructed.

VERDICT

Overall, if it wasn’t obvious enough, U.S., or Uncle Sam is a fantastic read and one that everybody, a fan of comic books or otherwise, should definitely read. Darnall’s writing depicts a unique history of America that is entirely honest, and he writes Uncle Sam’s character brilliantly as a man from the past naturally disappointed at the future. Thanks to Alex Ross’s professional and fantastic art, the world that is constructed by the two of them comes to life and the product is probably, next to WE3, one of the best original Vertigo stories ever published.

Story: 9.5/10

Art: 10/10

Next Week: Batman and Son (Batman 655-658, 663-666). Written by Grant Morrison with art by Andy Kubert, and Jesse Delperdang.

Comments